From the lakes in Minnesota and the streams in Kansas and Nebraska to the Pacific Ocean off the shores of California and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, Husker biologist Rene Martin is chasing light.

Or, more specifically, bioluminescence and biofluorescence.

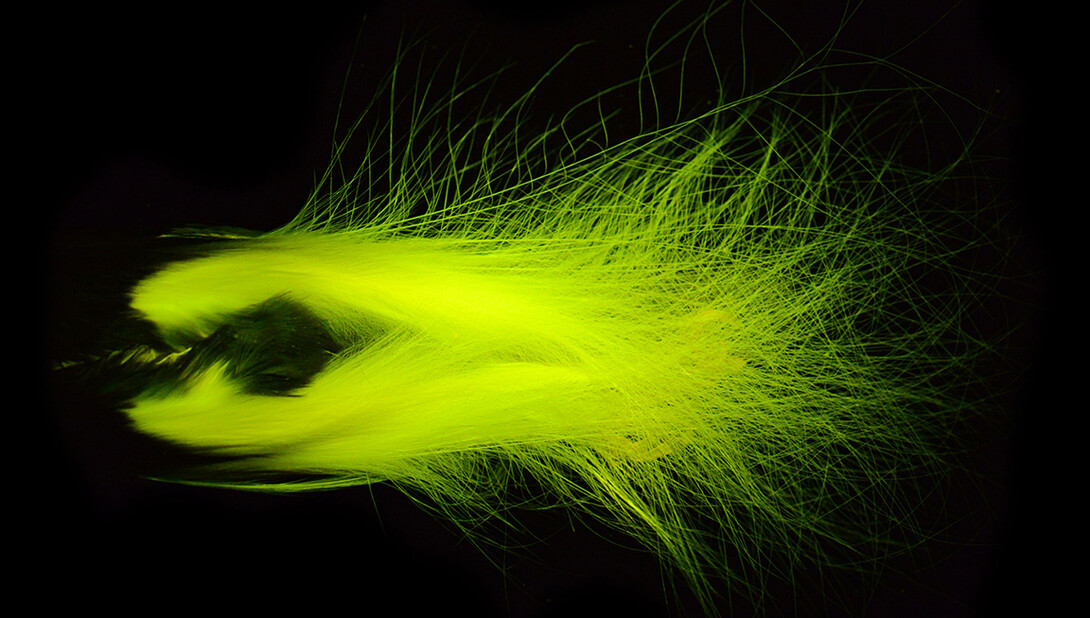

Martin, assistant professor in the School of Natural Resources, stepped into the global spotlight with her discovery of biofluorescence in birds-of-paradise. Her article published in the Royal Society for Open Science. By investigating specimens at the American Museum of Natural History, Martin discovered that 37 of the 45 known species use biofluorescence. The research was featured in dozens of outlets, including The New York Times, the Guardian, Forbes and Smithsonian Magazine.

“I think people like flashy things, and that’s what a bird-of-paradise is, and now we know they’re also glowing,” Martin said. “As more of these studies come out, often due to the availability of more advanced technology, I think we’re going to find out (bioluminescence or biofluorescence) is more prevalent than we thought.”

Martin was drawn to researching the glow of biological organisms as an undergraduate researcher at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota.

“I knew I was interested in science, and being from Minnesota, the land of 10,000 lakes, there were a lot of opportunities to work in fisheries, and I was enjoying all of it,” Martin said. “Then a new professor came in who happened to be working on deep sea luminescent fish, so I applied to work with him in his lab.

“I worked through my master’s and doctorate, researching deep sea fish, but also learned freshwater sampling skills, since I was also working in lakes and rivers.”

Martin is now teaching those research skills to her students through classes, labs and education abroad trips, such as the January trip to the Bahamas where students studied marine ecology alongside scientists from the Bimini Biological Field Station.

Martin’s research mostly pertains to lanternfishes, a small and abundant deep-sea luminescent fish. She is studying the evolution of the species, as well as the anatomy of light organs in multiple groups of bioluminescent fishes, including lanternfishes, ponyfishes and tubeshoulders. While some might assume that this work is difficult in a land-locked state, Martin said most of her work requires previously collected museum specimens and not deep-sea trawling.

The research on the birds-of-paradise was a bit of a happy accident. After finishing her doctorate at the University of Kansas, Martin applied for a post-doctoral fellowship at the American Museum of Natural History to further her research on lanternfishes, but her sponsor, John Sparks, approached her about also examining the birds-of-paradise specimens at the museum.

“He’d noticed that birds-of-paradise do this but hadn’t further pursued the work and asked if I was interested in researching and writing it,” Martin said. “I said ‘Yes, I would love to do this study.’ And then I got access to the ornithology collection.”

Using black lights, UV lights, a spectrophotometer and filter glasses, Martin examined the species of birds-of-paradise and was able to measure their biofluorescence.

“Birds-of-paradise are a well-studied group — they’re a hot topic — but we can still find new information,” Martin said. “This adds a component to the reproductive behaviors that these birds do and adds an additional piece to the puzzle.

“One discovery leads to asking more questions about these abilities in different groups. It may be part of their communication or camouflage or reproduction.”

Martin has also turned her inspecting eye toward local marine life. She’s mentoring students researching invasive carp and the human impacts on Nebraska’s fish populations. Martin is also planning to work with the University of Nebraska State Museum—Morrill Hall to trace fish populations in Nebraska through time.

“That work will probably focus on either how diversity of some of these fishes have changed through time and if that’s associated with human impacts like the creation of a dam or the straightening of a stream or a river, or looking also at morphological changes over time,” she said.