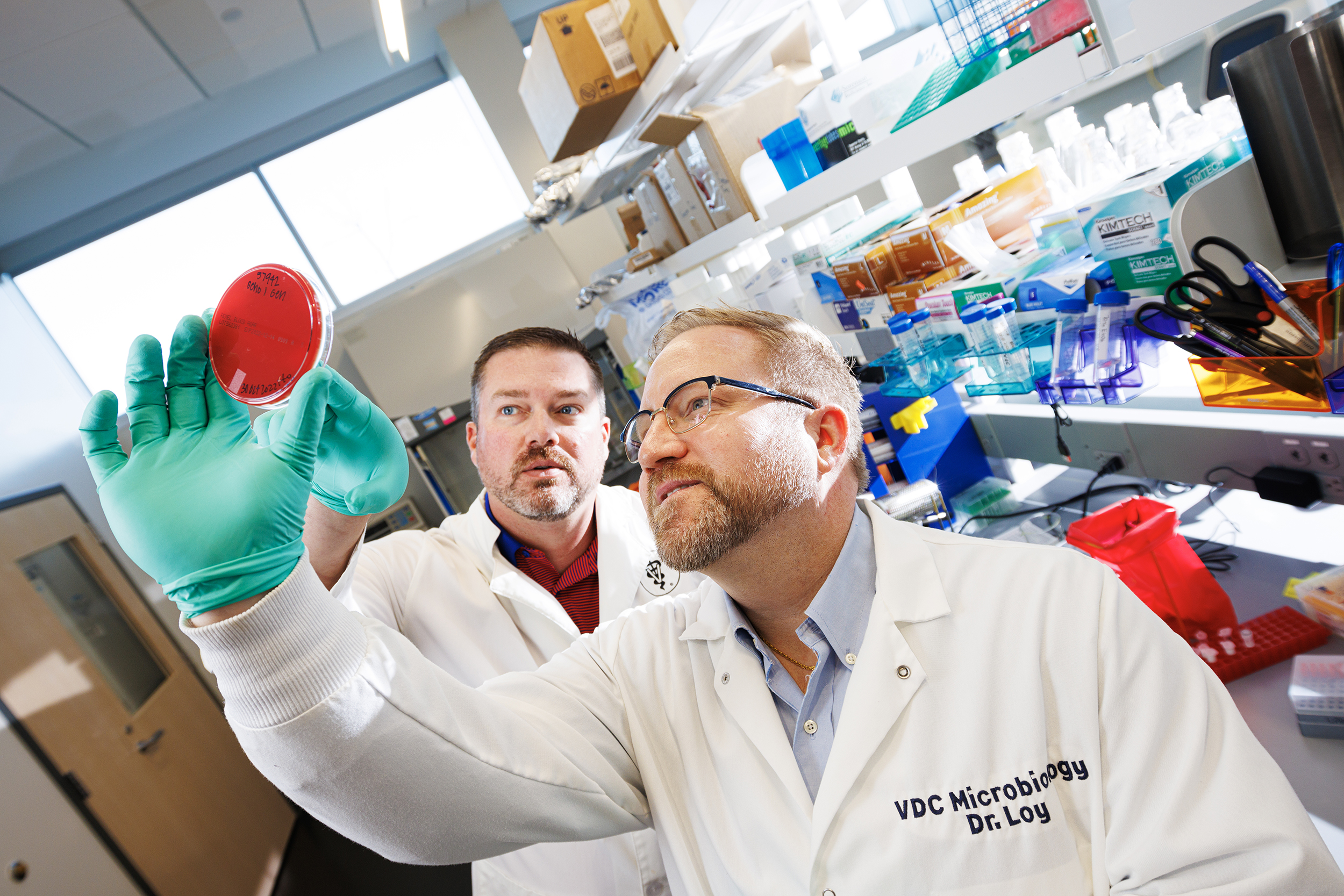

Research notes, reference materials, reports — such are the items to be found in the East Campus office of Dustin Loy, a professor in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. But Loy’s office also features an unusual drawing, a scientific one from deep in the university’s history.

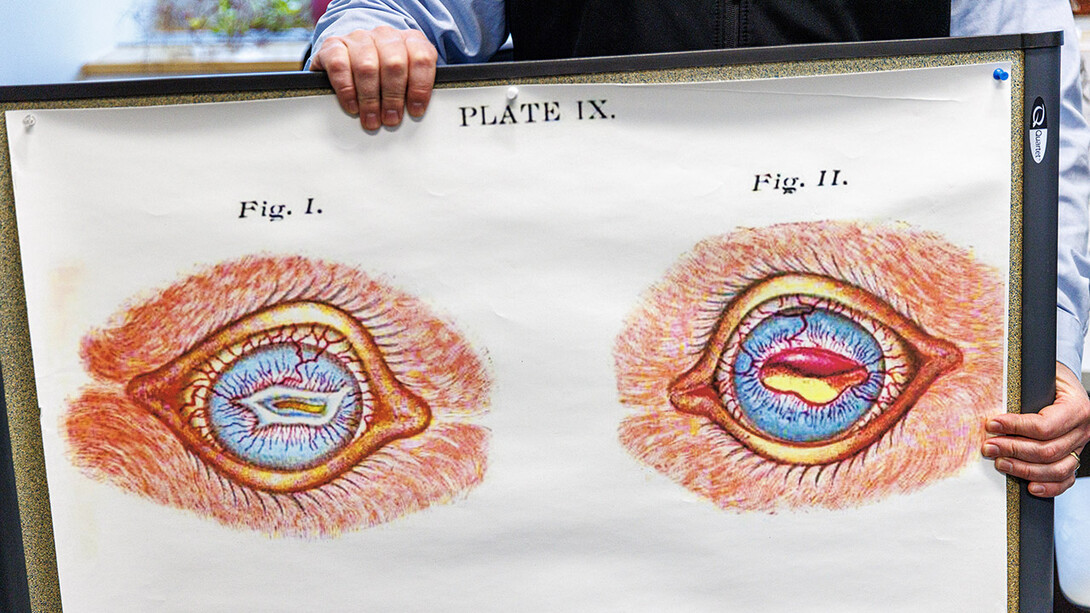

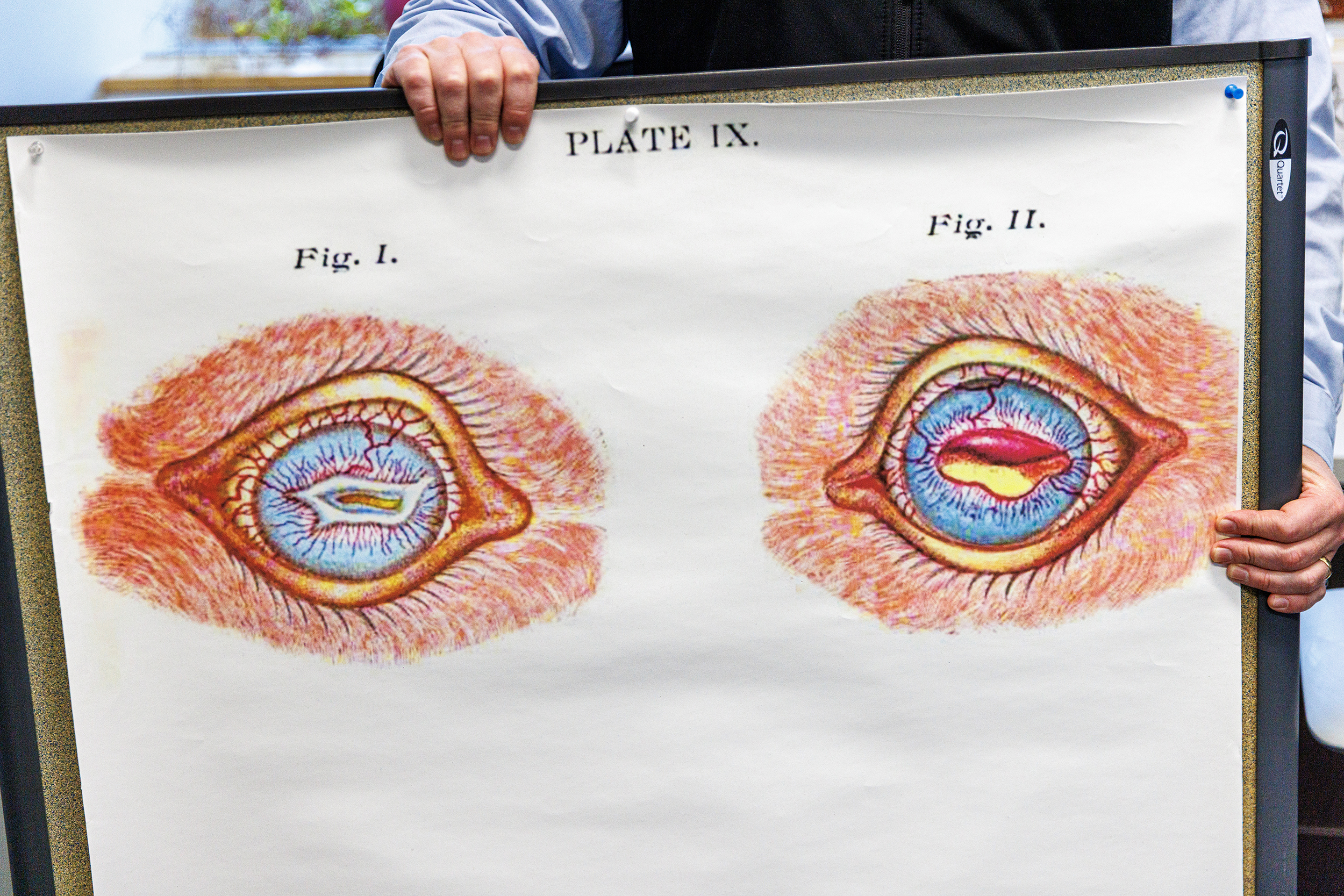

The image is a drawing from one of the first known descriptions of cattle affected with pinkeye, a longtime scourge of Nebraska beef producers. The debilitating disease is primarily caused by Moraxella bovis, a tiny organism that, in the 21st century, results in annual losses to the cattle industry estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Frank Billings, a veterinary pathologist who was the first NU faculty member given a full-time research position, sketched the image of afflicted cattle for an 1889 bulletin from the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. The bulletin, in which Billings described a “dense cluster of micro-organisms,” provided the first scientific description of the bacterium and the disease.

In the present day, combating bovine pinkeye — an affliction that involves a range of possible trauma to the animal’s eye — remains a major challenge for veterinary research scientists. The genetic diversity and variation of the bacterium are so complex that major gaps in scientific understanding remain. And unlike diseases such as polio and measles, which can be addressed through a vaccine, bovine pinkeye so far has remained resistant to consistently effective prevention via vaccination.

The illness — technically, infectious bovine kerato-conjunctivitis, or IBK — is the No. 1 reported disease for breeding cows and No. 2 for calves.

Two recent studies with contributions from Husker researchers are advancing scientific knowledge of the disease. A joint research project between the university and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service, or ARS, reported important findings about the bacterium’s genetic characteristics. And Matt Hille, an assistant professor of veterinary medicine and biomedical sciences, headed the first long-term study of bovine pinkeye vaccines, identifying shortcomings in inoculation efficacy.

Finding a solution to bovine pinkeye is hindered by the fact that a range of factors, of varying influence, contribute to the incidence of the disease.

“It’s what we call a classic disease complex,” Loy said, “with contributions from the pathogens, contributions from the host — we know that certain breeds or types of animals are more susceptible to this disease than others. And then there’s the environment, everything from dust to UV light to fly burden. All those things contribute. So, there are a lot of targets.”

“A big factor, certainly, is that this is a multifactorial disease,” said Hille, whose vaccination study noted the multiple influences contributing to the disease.

The genetic complexity and variability of the M. bovis bacterium — as well as a related bacterium, M. bovoculi — at present thwart a complete understanding of the microorganisms’ ability to cause disease. Precisely which factors turn non-threatening components of the bacteria into pathogens have yet to be fully identified. Nebraska’s joint study with ARS, published in BMC Microbiology, has moved the science forward by providing significant new information on the genetic structure and diversity of M. bovis.

ARS molecular biologists Emily Wynn and Mike Clawson, at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Nebraska, analyzed M. bovis strains provided by Loy from the university’s extensive inventory of pinkeye bacterial isolates. Loy collected the samples from veterinarians in 17 U.S. states and one Canadian province as part of his longtime work in identifying variabilities among the strains.

The ARS scientists sequenced and compared the samples’ genetic makeup, resulting in notable discoveries. The researchers identified two major M. bovis genotypes, each with different versions of a pinkeye-related toxin. They also identified certain proteins on the outer membrane of the bacterial cell.

Those findings significantly broaden scientists’ genetic understanding of the disease. This sets the stage for future research work to fill in additional gaps, to enable “better interventions and better targets,” Loy said.

The joint project is the latest in scientific collaboration by the university and ARS in recent years on cattle-related diseases.

In an academic paper published this year in the journal Vaccines, Hille described a five-year study he headed that compared pinkeye vaccine effectiveness for three study groups of calves. One group received an autogenous vaccine, developed from bacterial strains isolated from the study herd. Another group received a commonly used vaccine developed by a pharmaceutical company. A third group received a formulation consisting only of adjuvant, a component normally added to a vaccine to bolster the immune response.

The autogenous vaccine produced a significantly stronger antibody response than the other two formulations, but the effect wasn’t significant in terms of actually preventing the disease. The study involved an average of 240 calves a year at Nebraska Extension’s Eastern Nebraska Research, Extension and Education Center near Mead.

Hille’s five-year project advanced the science in several ways, Loy said. It was the first vaccine study using real-world field conditions over that duration of time and that used antigens from three different species of bacteria associated with pinkeye. It stands out, too, because Hille, in collaboration with virologist Hiep Vu of Nebraska’s Department of Animal Science, developed an analytical approach examining the animals’ immune responses and whether they came down with the disease.

Other contributors to the project were Matthew Spangler, with the Department of Animal Science, and Kelly Heath, with the School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Related Links

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS