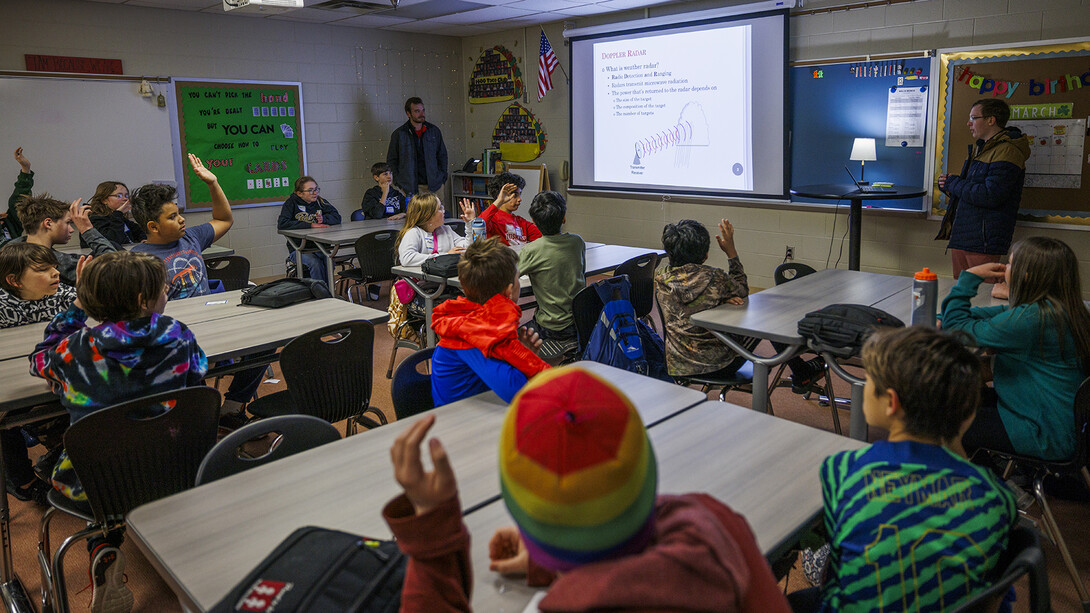

Sixth-graders got a glimpse of real-world weather science March 20 and 22 when University of Nebraska–Lincoln meteorology researchers visited several middle schools in the Millard Public Schools district.

Graduate students Ben Schweigert of Omaha, Ben Moll of Seward and Charles Kropiewnicki of Mullica Hill, New Jersey, visited three middle schools March 20 to give students an up-close look at the university’s specially built storm-tracking vehicles and to teach a brief lesson about how storms are studied. Kropiewnicki, Schweigert and Mark De Bruin, a graduate student from Pella, Iowa, were to visit three more Millard middle schools on March 22.

Severe Weather Awareness Week in Nebraska is March 25-29. In the past two decades, tornadoes in the United States have caused more than 1,600 deaths, more than 23,000 injuries and nearly $31 billion in damage.

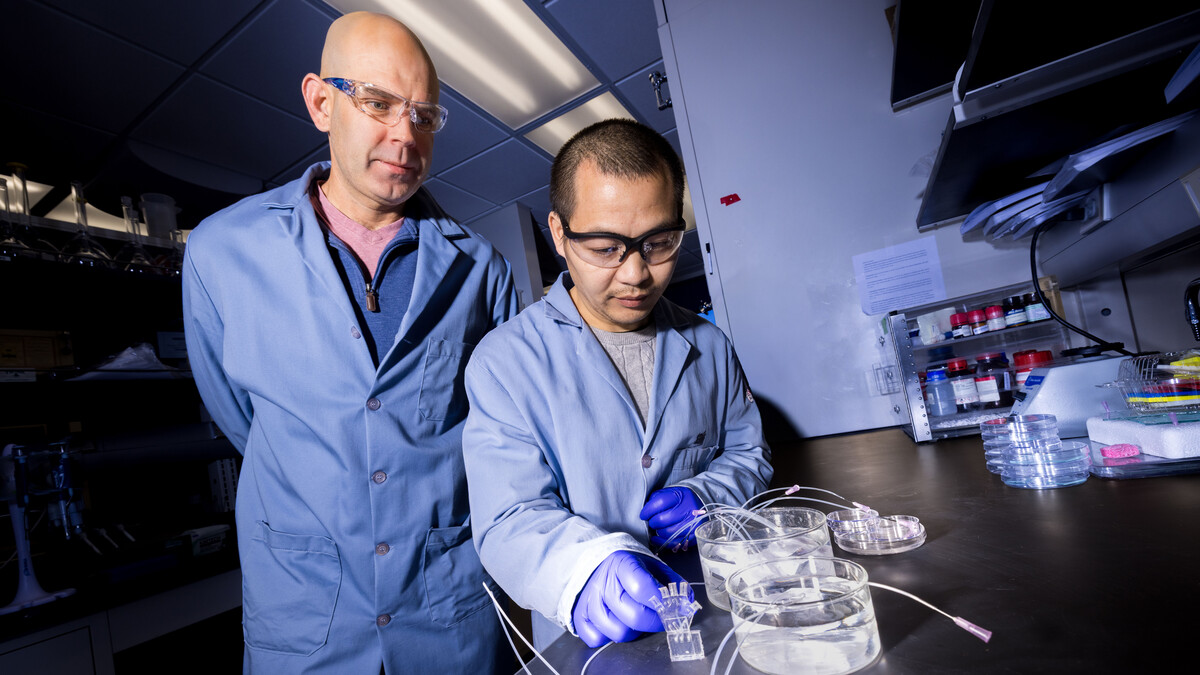

The researchers are among Husker scientists who have traveled across the Great Plains in recent years, using fixed-wing drones and other high-tech equipment to investigate how tornadoes form during supercell thunderstorms.

They pulled up at the schools in CoMeT2 and CoMeT3 — Ford Explorer sport utility vehicles modified to serve as storm-tracking mobile laboratories.

They warned the students just how violent tornadoes, thunderstorms and lightning can be, and how fast supercell storms can move.

“You should not go storm chasing unless you have the training to do so,” Schweigert told the group at Millard’s Russell Middle School on March 20.

“Tornadoes can change direction and speed in an instant,” Kropiewnicki said. “You won’t have time to react.”

About 20 Russell students divided into two groups to closely examine the vehicles. Schweigert pointed out the anemometers mounted atop the vehicles, along with tubes containing gauges to measure air pressure, temperature and relative humidity. He also noted the wire mesh panels atop the cars, to protect the windshield from shattering during hailstorms.

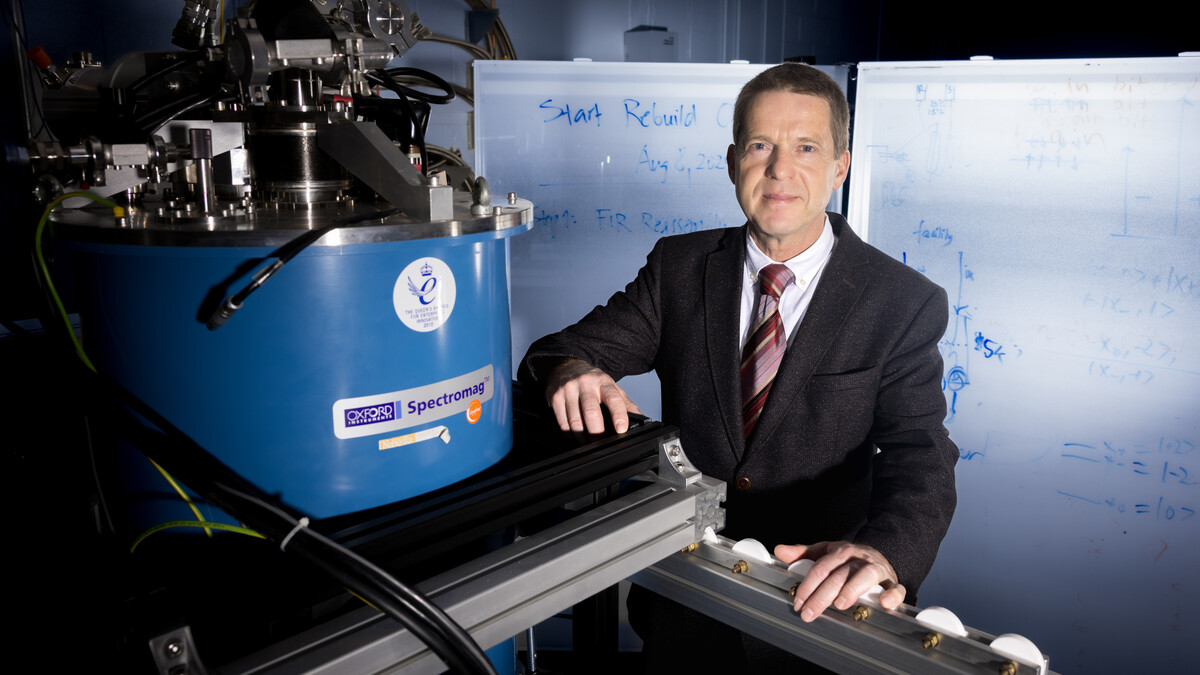

All in their early to mid-20s, the young scientists who came to the Millard schools participated in field research campaigns for the TORUS project led by Adam Houston, professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences at Nebraska. Kropiewnicki is a doctoral student advised by Houston, while the others are studying for master’s degrees.

TORUS, or Targeted Observation by Radars and UAS of Supercells, was a seven-year project that used drones and tracking vehicles to gather new data about supercell thunderstorms. Houston was a principal investigator for the project. Other participating institutions were the University of Colorado, Boulder, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Severe Storms Laboratory, the University of Oklahoma Cooperative Institute for Severe and High-Impact Weather Research and Operations and Texas Tech University.

Schweigert, an alumnus of Millard Public Schools, said he was surprised and pleased by the youngsters’ enthusiastic response to the storm-chasing vehicles.

“Even though it was chilly outside, they were engaged and interested in the vehicles and brought terrific questions,” he said.

“Whoa!” and “Yummy!” someone exclaimed, prompting a laugh from Kropiewnicki as he opened up the hatchback to show the computer racks, equipment cases and batteries stowed at the back of the car.

Most of the youngsters raised their hands when asked if they had flown drones themselves. Their experience, however, was with the commonly used four-propeller quad-copters, while the drones used in TORUS look more like small airplanes, with fixed wings measuring seven-and-a-half feet from tip to tip. That led the students to ask how the drones fit into an SUV-sized vehicle. They were told that the wings detach for transport.

“I was surprised by the number of students who asked us whether we used the hail cages as landing pads for drones,” Moll said. He and the others explained that the drones used for weather research are typically landed in open areas with sufficient space to slide to a stop.

Other questions included how many tornadoes a storm can generate, how large tornadoes can be and how fast they can move. The answers: Thunderstorms do generate multiple tornadoes over the course of their existence, but usually not simultaneously; the largest tornado recorded was 2.6 miles wide; and the top speed for forward movement was 94 mph.

Husker alumna Amanda Taylor, who is a high ability learner facilitator and literacy coach at Russell Middle School, worked with Houston to arrange weather “seminars” at the six schools.

The researchers visited Millard’s North, Andersen and Russell middle schools on March 20 and Central, Beadle and Kiewit middle schools on March 22.

“Students study weather patterns in sixth-grade science classrooms,” she said. “They are very interested in weather, and this gives them a chance to learn about real-world weather careers.”

Taylor’s brother, Nick Wiltgen, also a Husker alumnus, was a meteorologist with the Weather Channel when he died in 2016. To honor her brother’s passion for weather, the Wiltgen family established an annual award for the top Husker meteorology graduate student as selected by program faculty. Kropiewnicki was this year’s winner.

Houston said outreach to young students is an important element of the university’s science programs.

“Nurturing or sparking a passion for science is important for supporting the development of the next generation of scientists,” he said. “Moreover, by talking about weather, I hope they gain an appreciation and respect for the natural world.”