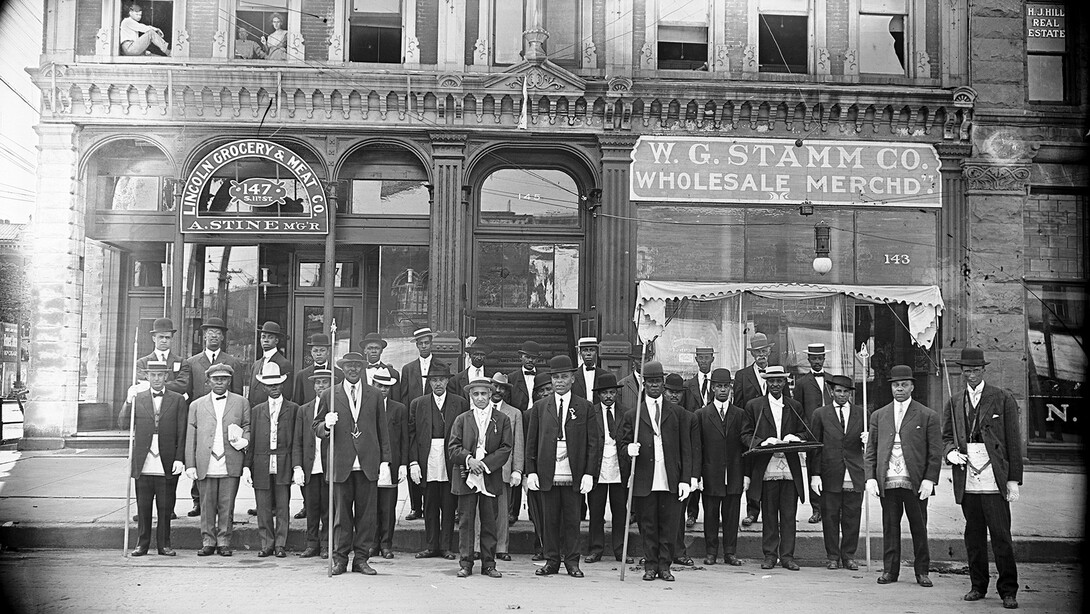

Once lost to time, the photography of Nebraska’s John Johnson is back in focus as a unique view into the Lincoln-area’s Black community in the early 1900s.

Primarily between 1912 and 1925, the once University of Nebraska student and football player captured some 500 black and white photographs featuring family portraits, parades, building sites and spot news (including a 1910 train wreck at the corner of 25th and E streets).

Johnson was born in Lincoln in 1879 to Harrison (a runaway slave and Civil War veteran) and Margaret Johnson. He graduated from Lincoln High School in 1899, after which he attended the University of Nebraska for several semesters. While he never graduated, Johnson was active on campus as a member of the university football team — a time when the mascot was changing from the historic Bugeaters to iconic Cornhuskers.

After leaving the university, Johnson settled into a career as a laborer — including time as a post office janitor and beer delivery person. Conversely, Johnson’s work as a community photographer offers a masterful grace as it integrates high contrast between black and white, use of negative space to define compositions, and deftly handled use of natural light.

Johnson’s portraits are significant as they show Black families from the region (primarily in Lincoln, Omaha and Kansas City) regally posed and most-often in formal clothing. They differ from the majority of photos from the same era, which cataloged how the Black community lived in poverty and were treated as second-class citizens.

Johnson lived with his widowed mother until the early 1920s. He married widow Odessa Price in 1918. The couple, both of whom died in 1953, had no children.

In 1938, Johnson created “Negro History of Lincoln 1888-1938,” a listing of the Black residents of Lincoln alongside their occupations. The publication was part of a National Negro History Week event.

After his death, the glass negatives of Johnson’s photos were lost to time. They were rediscovered in 1999 when Douglas Keister, a California photographer (and former Lincoln resident), connected a Lincoln Journal-Star story with a heavy box of 280 antique glass-plate negatives he had purchased at a rummage sale.

Today, Johnson’s images are considered a precursor to the Harlem Renaissance, an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship that spanned the 1920s and 1930s (an era that also featured Nebraska U artist Aaron Douglas). His photographs are featured in multiple museum collections, including the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Nebraska Art in Kearney.

Johnson’s story has been featured by the Smithsonian as well as other national publications.