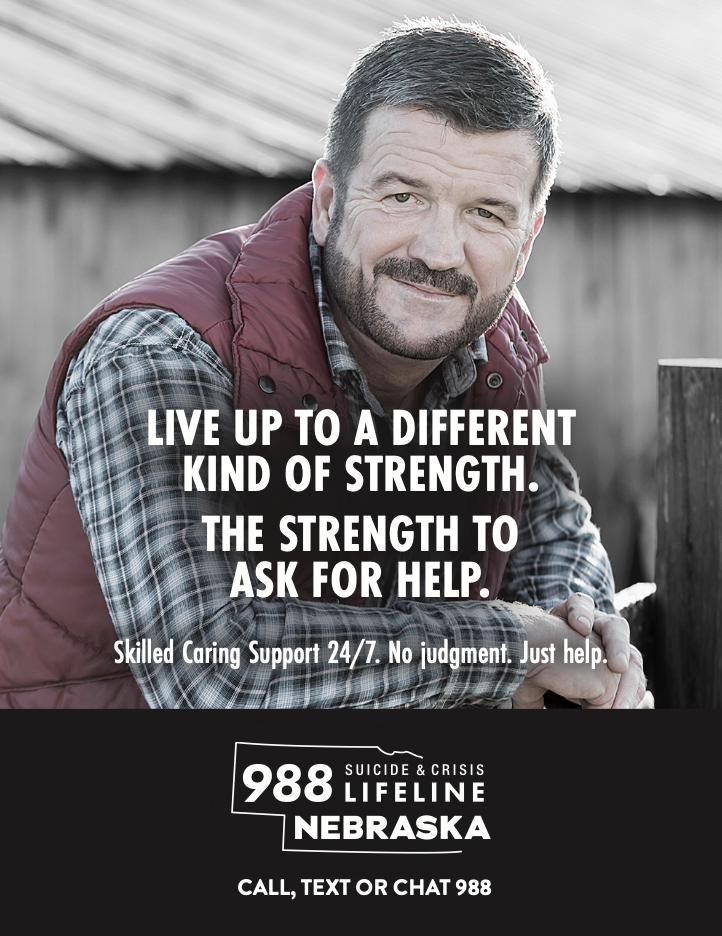

Across Nebraska, new suicide prevention posters are appearing with a simple, powerful message for rural men: “Live up to a different kind of strength. The strength to ask for help.” Featuring everyday men in familiar settings, the materials direct people to call, text or chat with 988, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

After reaching millions through statewide TV, radio and digital ads, the campaign has expanded on the ground, sending materials to 82 Nebraska Extension offices to reach local gathering spots like coffee shops, co-ops, meatpacking plants and pesticide training sessions.

The majority of the state’s suicide prevention work in the past has focused on youth and young adults, with the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center assisting an array of organizations with data collection and analysis to ensure programs were evidence based and to measure success.

“When we looked at the data, the population at highest risk of suicide was adult males, 25 to 64, a different population we had not routinely focused on,” Denise Bulling, senior research director at the Public Policy Center, said.

An analysis revealed that Nebraska rural men die by suicide at nearly 2.5 times the rate of their urban counterparts. Rural suicide deaths amount to 38.6 per 100,000 men compared to 16.1 per 100,000 in Lincoln and the Omaha metro.

Now for the third year, the center is working with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nebraska Health and Human Services, Behavioral Health Regions, Nebraska Extension offices and the Nebraska State Suicide Prevention Coalition to promote suicide prevention across the state.

The Public Policy Center is highlighting suicide prevention this fall as various mental health awareness weeks are scheduled. The center also co-sponsored a National LOSS (Local Outreach to Suicide Loss Survivors) Conference Oct. 13-15 in Nebraska. Local LOSS teams of volunteer clinicians and suicide loss survivors, notified after a suicide, reach out to family and friends to offer support and connection to local resources.

The timing coincides with recent headlines about economic stresses rural families are experiencing, said Quinn Lewandowski, a research manager at the Public Policy Center. As former rural kid himself, he's eager to break down stigma and get more people to recognize when they or someone they know is struggling and to learn where to turn for help.

“The data doesn’t lie,” Lewandowski said. “It’s really important we have these conversations. It’s tough to be the person in the family everyone looks to for support, the provider, and admit that stress can add up quickly.”

He said the main message is help can be as easy as a phone call away at 988 or a telehealth provider. (To find one, visit the Health and Human Services telehealth website). But he and Bulling said they aim to get information more “upstream” by giving people the tools they need for early recognition of an issue for themselves or someone else before it’s a crisis.

For example, one poster reads: “Know the warning signs of suicide. Depression. Isolation. Agitation. Talks about suicide. Acquires suicide methods. Previous suicide attempts. Help is available 24/7 at 988.”

Another featuring two men with a hunting dog reads: “Taking care of friends and neighbors … it’s what we do in Nebraska. If you know someone who’s thinking about suicide, talk to them about temporarily storing their guns away from home. ... Call, text or chat 988.”

Brochures outline ways to secure firearms, medications and other means of suicide in a way that allows time for a change of heart or for someone else to intervene. Secure lockboxes and cable locks are being distributed across the state. Beth Nacke, rural health educator for Nebraska Extension, said the suicide prevention materials seemed to be well received when she and Lewandowski were at Husker Harvest Days.

“We had some really great conversations with people who were pretty candid with experiences they had or they had with family members or friends,” Nacke said.

She said women were more likely to engage, but the more impactful, detailed stories came from men.

“The ultimate goal is that it becomes normal to talk about mental health and well-being,” she said.

This is also the last year of a suicide prevention grant at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln that highlights a partnership on campus with the Public Policy Center, Counseling and Psychological Services and Campus Recreation. A key suicide prevention awareness training is part of that program. It is sustainable because the curriculum is owned by the university, said Mariah Johnson, outreach and suicide prevention coordinator.

The program offers regular training sessions to students, faculty and staff designed to increase awareness of behaviors associated with elevated suicide risk, learn what to do and say when encountering someone at risk of suicide and know where to get help on campus.

Learn more about suicide prevention efforts in Nebraska.