Willa Cather is among the most well-known Nebraskans, and her hometown of Red Cloud is a central character in many of her novels, with intricate descriptions of the prairie and many of its people.

With that in mind, Cather researchers at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln welcomed 24 scholars to a two-week institute, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and held July 16-28. The institute, “Willa Cather: Place and Archive,” gave the scholars the opportunity to experience first-hand the places that informed Cather’s literature and grapple with some questions Cather left unanswered in her work and letters — namely the colonization of the American West and the forced relocation of Indigenous people.

Melissa Homestead, professor of English and director of the Cather Project at Nebraska, explained that though Cather lived in Red Cloud as a child and fictionalized many of the people she knew and the events she experienced, she didn’t include the Pawnee, who had most recently lived on the land where Webster County is now located.

“We were particularly interested in thinking about what isn’t in Cather’s fiction set in Nebraska, particularly the Pawnee, who occupied the land where Webster County and south-central Nebraska is,” said Homestead, the principal investigator for the institute. “Cather cast them in the distant past, when in reality, they were recently relocated to the north of the Platte River, and they still came down when the earliest members of the Cather family came from Virginia in 1873. They were still hunting in Webster County. We’re thinking about what it means that they’re not there (in Cather’s work).”

Among the sessions offered were talks from Walter Echo Hawk, a Pawnee leader, lawyer and novelist, and Margaret Jacobs, Charles Mach Professor of History, who has researched the relocation of Indigenous Americans. Both spoke about the forced relocations, the cultural genocide that occurred in Indian Boarding Schools and the legal fight to regain remains from institutions.

“While Cather was a child, and then later when she was an adult returning to Webster County, people were routinely digging up the remains of Pawnee people,” Homestead said. “She had to have known that, but it’s not something that she grapples with really at all in her fiction on the Great Plains.”

An additional full slate of sessions with Cather and digital humanities experts took the scholars to Homestead National Historical Park in Beatrice, the National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud and into the Archives and Special Collections at the university.

“We wanted to get people to Nebraska to experience the places that Cather fictionalized and offer them the opportunity to use both paper and digital collections to experience Cather through them, and recognize that those two things work together,” Homestead said.

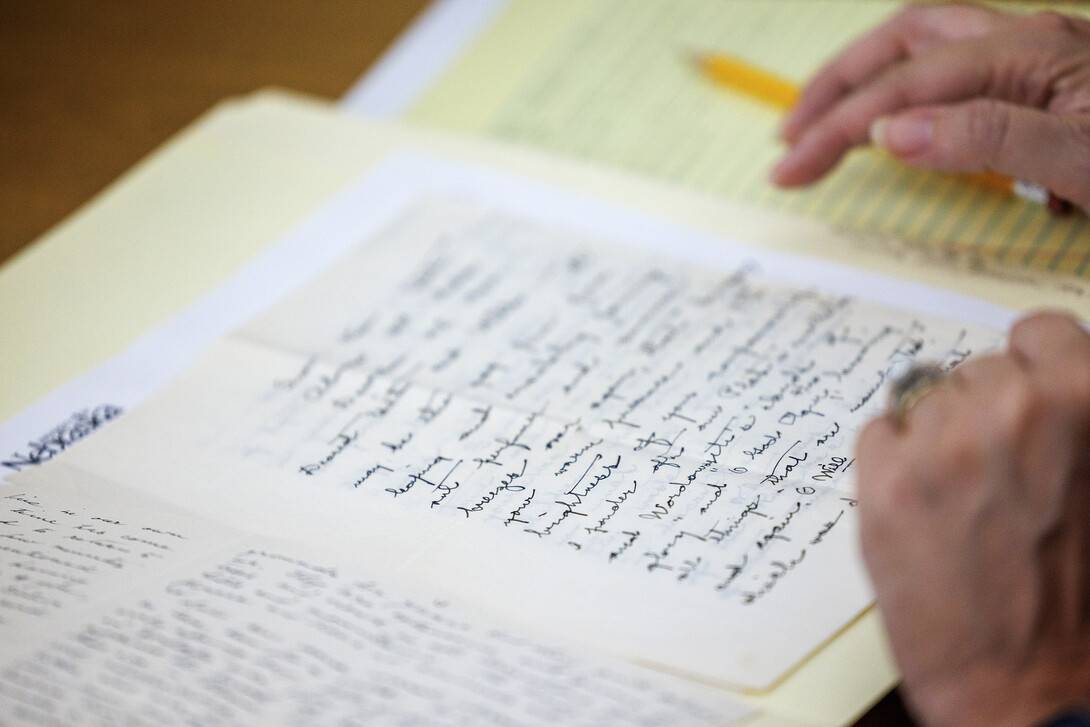

Participants returned to Lincoln for the second week, where they were able to spend time with Cather’s letters and manuscripts and heard from scholars who have used the letters in new and surprising ways in research since the letters were digitized and annotated through the Complete Letters of Willa Cather, hosted by Nebraska’s Center for Digital Research in the Humanities. They also gained new insights into how to use digitized records for research and pedagogy.

The institute welcomed not only Cather scholars, but many with an interest in digital humanities. Dominic Dongilli attended because he is a Nebraska native, humanist and doctoral student in American studies and gender, women and sexuality studies at the University of Iowa.

“What excited me about this institute was the possibility to connect my own personal history and personal interests to things that I also encounter in my research and formal classroom education,” Dongilli said. “The opportunity to think and speak and be in community with a diversity of people who are all brought here for a number of reasons was confirmation — a reminder — and rejuvenating in a way, to think about how these things brought Willa Cather and her community together. Those same things still continue to bring us and our communities together and help us understand the experiences that we’re going through.”

Rachel Collins, an assistant professor from Arcadia University in Pennsylvania, is a Cather scholar and has published work about Cather’s use of place. She was grateful for the opportunity to spend time in the places that inspired so much of Cather’s literature.

“The focus I take in my research is largely spatial — I would position it within the geo-humanities,” Collins said. “The notion of spending two weeks thinking about spatiality in relationship to Willa Cather was just really appealing to me. It was my first time in Nebraska, and I feel like it has been enormously illuminating to me.”

Collins also gained some new ideas in how to use digitized records in her classes to open up new ways of thinking about historical fiction for her students. A session led by Evelyn Funda dove into Census records and aerial photographs to track the migration of Czech settlers, including the family of Anna Sadilek Pavelka, who was the prototype for the title character of Cather’s “My Antonia.”

“I might do some work with my students looking at aerial photography of settlement patterns and thinking about how our built environment impacts our social relations,” Collins said. “It was exciting to look at Census records and follow the Pavelka family, their experience as it was recorded. The data included not only the people, but the type of crops they planted and the livestock they raised. It brought some rich texture to the scenes and lives we encounter in Cather’s fiction and the material conditions of their lives.”

The institute wrapped July 28 with a roundtable discussion on pedagogy. Participants who wanted to present on their research or curriculum ideas were also given an opportunity in the closing session.