Little life could endure the Earth-spanning cataclysm known as the Great Dying, but plants may have suffered its wrath long before many animal counterparts, says new research led by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

About 252 million years ago, with the planet’s continental crust mashed into the supercontinent called Pangaea, volcanoes in modern-day Siberia began erupting. Spewing carbon and methane into the atmosphere for roughly 2 million years, the eruption helped extinguish about 96 percent of oceanic life and 70 percent of land-based vertebrates — the largest extinction event in Earth’s history.

Yet the new study suggests that a byproduct of the eruption — nickel — may have driven some Australian plant life to extinction nearly 400,000 years before most marine species perished.

“That’s big news,” said Christopher Fielding, lead author and professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences. “People have hinted at that, but nobody’s previously pinned it down. Now we have a timeline.”

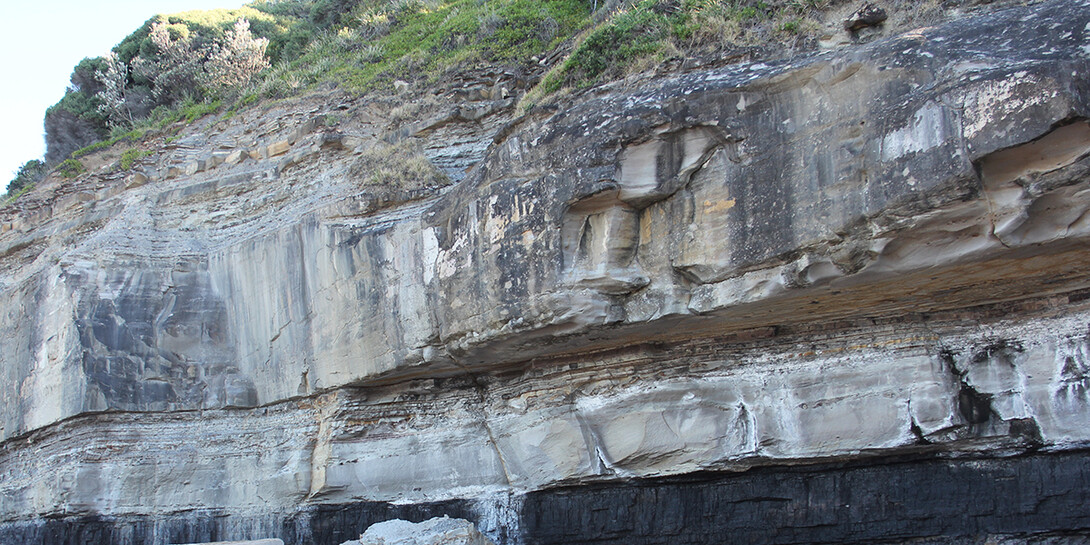

The researchers reached the conclusion by studying fossilized pollen, the chemical composition and age of rock, and the layering of sediment on the southeastern cliffsides of Australia. There they discovered surprisingly high concentrations of nickel in the Sydney Basin’s mud-rock — surprising because there are no local sources of the element.

Tracy Frank, professor and chair of Earth and atmospheric sciences, said the finding points to the eruption of lava through nickel deposits in Siberia. That volcanism could have converted the nickel into an aerosol that drifted thousands of miles southward before descending on, and poisoning, much of the plant life there. Similar spikes in nickel have been recorded in other parts of the world, she said.

“So it was a combination of circumstances,” Fielding said. “And that’s a recurring theme through all five of the major mass extinctions in Earth’s history.”

If true, the phenomenon may have triggered a series of others: herbivores dying from the lack of plants, carnivores dying from a lack of herbivores, and toxic sediment eventually flushing into seas already reeling from rising carbon dioxide, acidification and temperatures.

‘It lets us see what’s possible’

One of three married couples on the research team, Fielding and Frank also found evidence for another surprise. Much of the previous research into the Great Dying — often conducted at sites now near the equator — has unearthed abrupt coloration changes in sediment deposited during that span.

Shifts from grey to red sediment generally indicate that the volcanism’s ejection of ash and greenhouse gases altered the world’s climate in major ways, the researchers said. Yet that grey-red gradient is much more gradual at the Sydney Basin, Fielding said, suggesting that its distance from the eruption initially helped buffer it against the intense rises in temperature and aridity found elsewhere.

Though the time scale and magnitude of the Great Dying exceeded the planet’s current ecological crises, Frank said the emerging similarities — especially the spikes in greenhouse gases and continuous disappearance of species — make it a lesson worth studying.

“Looking back at these events in Earth’s history is useful because it lets us see what’s possible,” she said. “How has the Earth’s system been perturbed in the past? What happened where? How fast were the changes? It gives us a foundation to work from — a context for what’s happening now.”

The researchers detailed their findings in the journal Nature Communications. Fielding and Frank authored the study with Allen Tevyaw, graduate student in geosciences at Nebraska; Stephen McLoughlin, Vivi Vajda and Chris Mays from the Swedish Museum of Natural History; Arne Winguth and Cornelia Winguth from the University of Texas at Arlington; Robert Nicoll of Geoscience Australia; Malcolm Bocking of Bocking Associates; and James Crowley of Boise State University.

The National Science Foundation and the Swedish Research Council funded the team’s work.