After 12 years of diligent work by tribal people and University of Nebraska-Lincoln scholars, one piece of the revitalization of the Omaha Native language is complete.

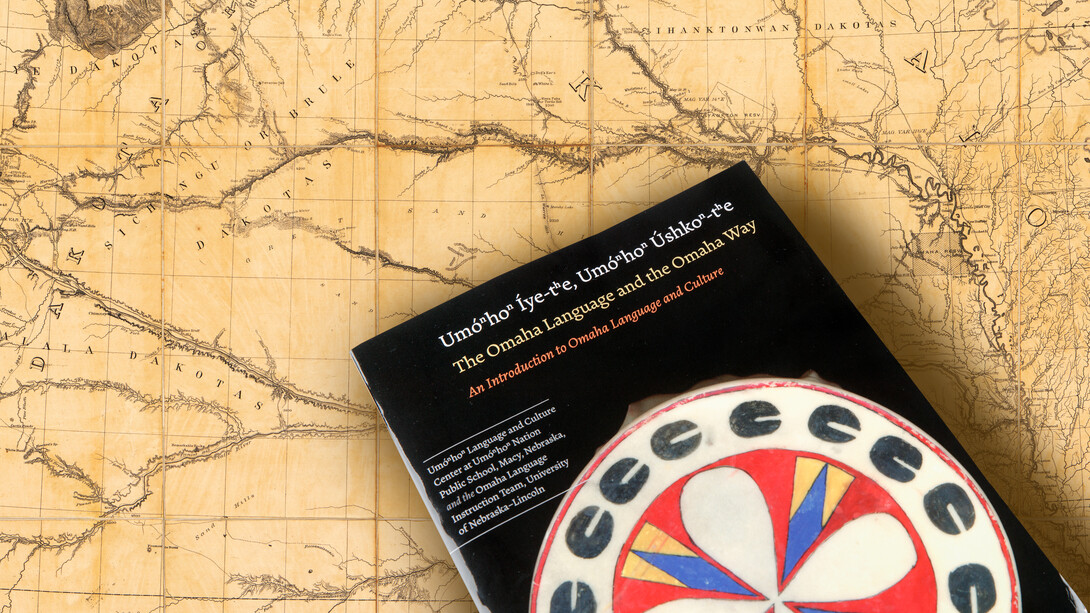

A comprehensive textbook, “The Omaha Language and The Omaha Way, Umóⁿhoⁿ Iye-tʰe, Umóⁿhoⁿ Ushkóⁿ-tʰe,” was published in August by the University of Nebraska Press. It was the last work of University of Nebraska-Lincoln anthropologist Mark Awakuni-Swetland, who died in 2015 after a 15-year battle with leukemia.

The project began formally in 2006, when Awakuni-Swetland worked with Elders of Omaha Nation to contract with the University of Nebraska Press to complete the book, with copyright and proceeds under the ownership of the Umóⁿhoⁿ Nation Public Schools Language and Culture Center.

The book is a resource for many levels in Omaha language learning and proficiency. Contributors to the book said lessons span from kindergarten through college-level coursework.

The documentation of the language and ways of teaching it began many years before, though, said Vida Stabler, Omaha member and director of the language and culture center who worked alongside Awakuni-Swetland and Elder contributors on the project. Stabler said the Omaha people have worked to pass on their traditions, culture and language to youths following the efforts by the U.S. government to assimilate Native youths through boarding schools in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These boarding schools nearly extinguished indigenous languages.

“Even though the book officially started 12 years ago, I’ve been working on documentation with elders for 18 years now, and that is what is in the new book,” Stabler said.

Awakuni-Swetland, who taught the Omaha language at Nebraska with a team of Elders, wrote in the contributor notes of the book that while teaching these classes, “it became evident in following years that the UNL class needed a textbook…” and he had formed “a close collaborative relationship with the Umóⁿhoⁿ Language and Culture Center at Umóⁿhoⁿ Nation Public Schools.

“It was clear that they as well as the wider Omaha community could benefit from a textbook,” he continued.

Awakuni-Swetland’s team worked with Stabler’s team on the project. Eventually, the number of contributors grew to 14, with fluent speakers, educators and scholars working together. At the university, Aubrey Streit Krug, then a doctoral student in English and Great Plains Studies, Loren Frerichs and Rory Larson, both with Information Technology Services and former students of Awakuni-Swetland, were asked to join the effort.

The group was stunned by Awakuni-Swetland’s terminal prognosis in 2014, but the work carried on. LuAnn Wandsnider, professor and former chair of the Department of Anthropology, quietly worked behind the scenes to make sure resources were available to complete the book.

“The beauty of this textbook is that you had two programs under two institutions working diligently on committed teams at both places,” Stabler said. “Both teams worked together toward the same goal, which has come to fruition, so this is really a story of success, a story of unifying two teams and bringing their works together.”

Streit Krug said the experience was invaluable to her as a scholar and an educator. She received her doctorate in May 2017, and is now the director of ecosphere studies at the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas.

“It’s an example of how an academic publication can be led by a community and can help serve the educational needs of that community and can abide by the values of that community,” Streit Krug said.

Stabler said plans for the book’s use in the schools and community are being formed, and it will be an incredible resource going forward.

“Our language is so endangered that we need every resource that is available,” Stabler said. “And it’s not as simple as sitting down and typing something out. There are many considerations that have to be made in order to carry the knowledge and words of our Elders forward to our people, to our children.”

Frerichs said he hopes the book will impact the university and its students, as well.

“We’re hoping it’ll be used by Omaha Nation and eventually, here at Nebraska,” Frerichs said. “Since Mark’s death, unfortunately, we haven’t had a Native languages instructor.”

From an educational and scholarly standpoint, Larson – who has taken classes on more than a dozen different languages – said it is important to maintain all languages, and he’s thankful to have been a part of this effort.

“Every language is unique,” he said. “It has its own characteristics, and you can learn a lot about the cultural histories of the people that spoke them. Whenever you lose a language, you lose with it a whole cultural world.”