Plant breeders traditionally have focused on factors such as disease resistance, drought tolerance and ways to boost crop yields and the producer’s bottom line — all matters of practical importance. Recent research by Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources scientists shows the value of considering an additional factor: strengthening a plant’s ability to promote human health.

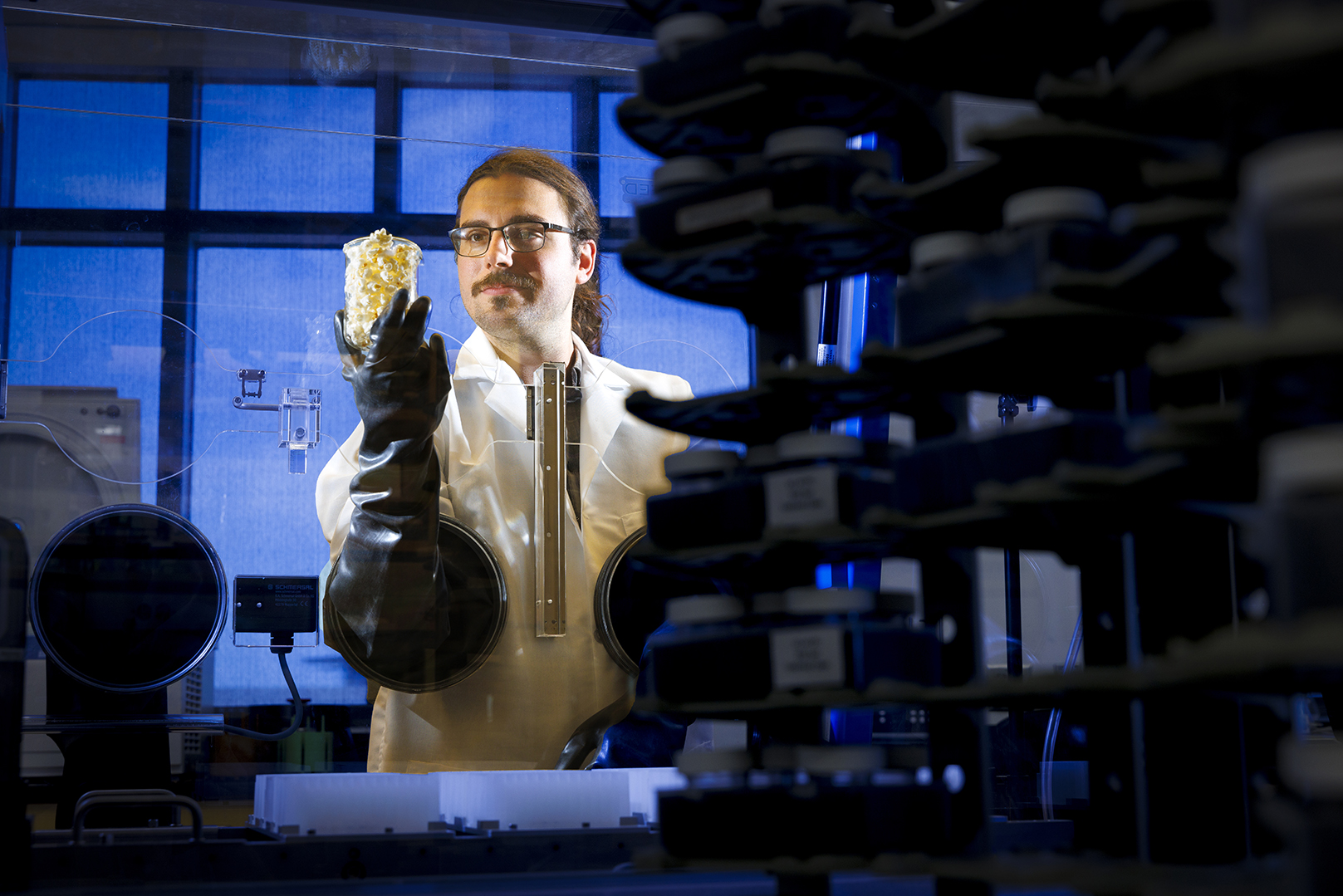

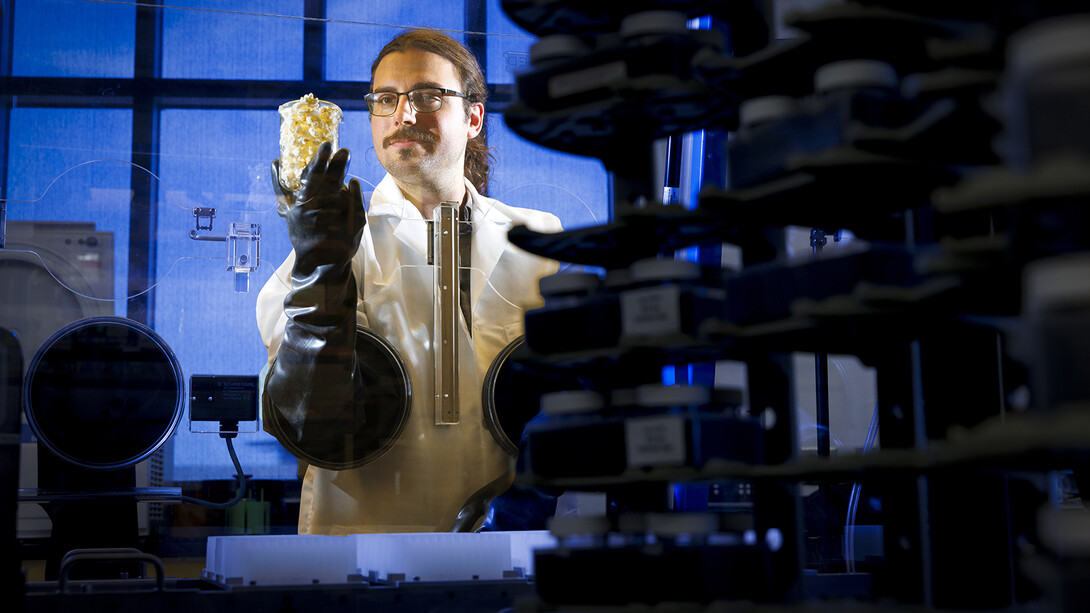

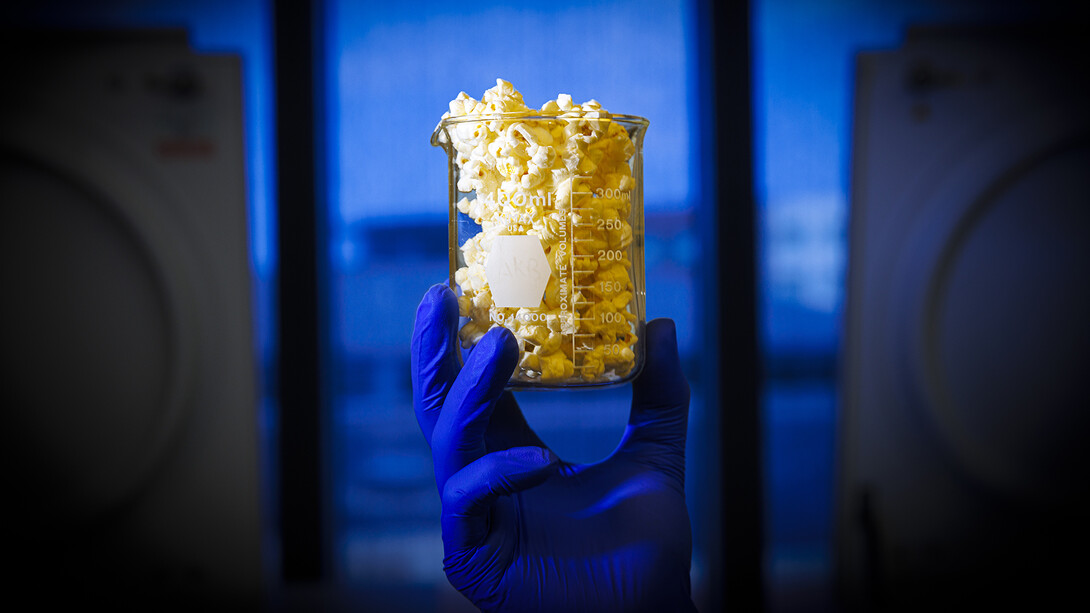

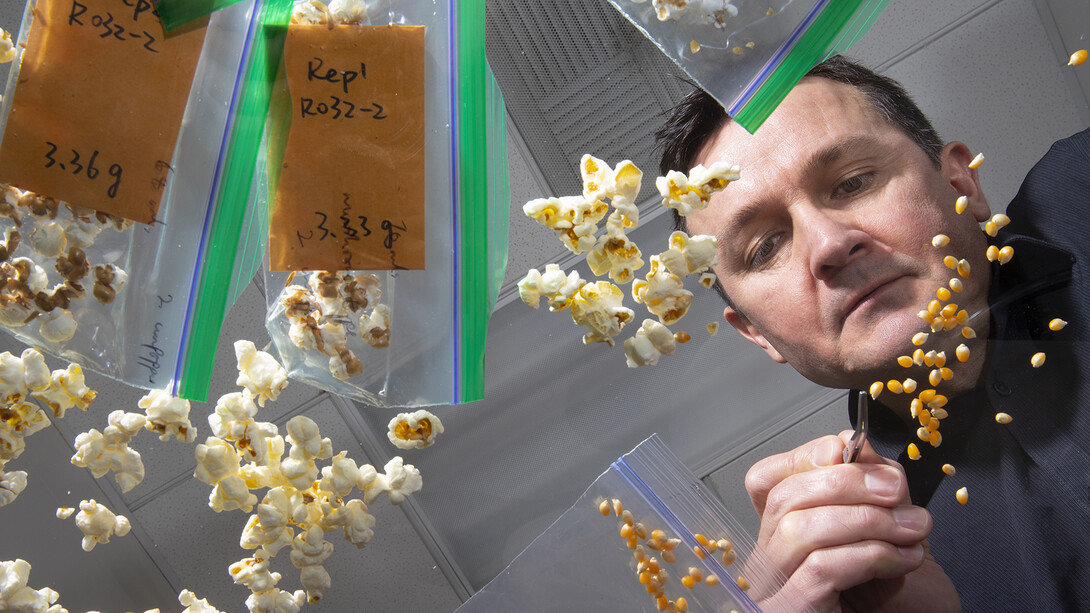

IANR researchers found that consumption of a new popcorn variety developed using conventional breeding techniques by David Holding, a professor with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Department of Agronomy and Horticulture, has a notably beneficial effect on the human microbiome, the complex community of bacteria in the human gut.

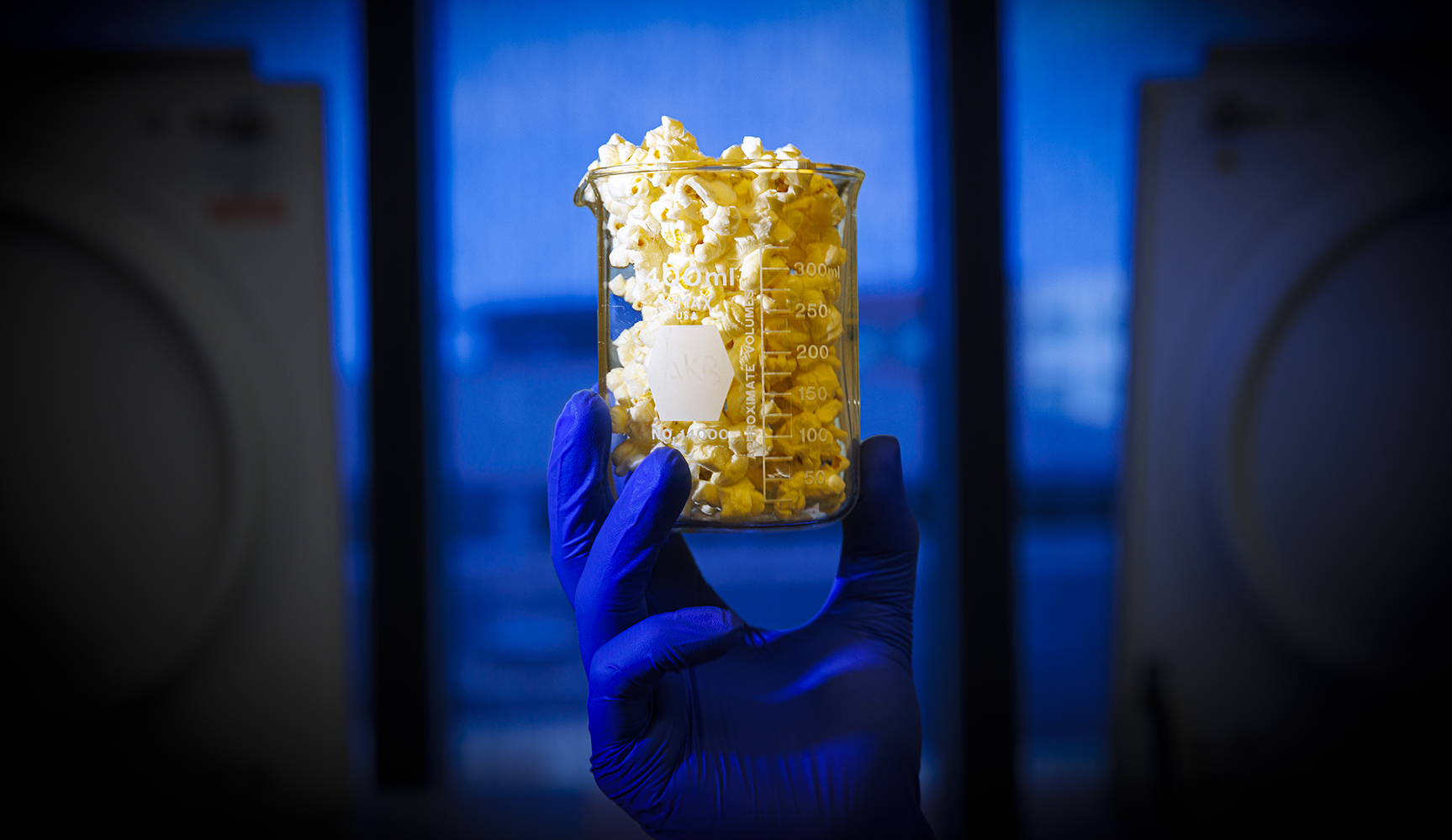

As the popcorn is digested, the microbiome responds by greatly increasing its production of butyrate, a “short-chain” fatty acid that boosts human health in major ways. Nate Korth, a doctoral student with Nebraska’s Department of Food Science and Technology and co-investigator in the research project, listed some benefits that butyrate facilitates: “Curbing appetite. Training the immune system. It’s used as sort of a communication molecule between the microbiome and the human body. It also has a role in sleep function.”

Human nutrition studies involving malnourished children have shown that higher production of butyrate by the microbiome resulted in increased physical growth rates and significant gains in height and body weight.

“When we introduce changes in plants, we’re usually thinking about the agronomic qualities” such as improved disease or drought resistance, but not about “how those changes are impacting the nutrition of the crops,” Korth said. The IANR project — whose findings were recently published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology — underscores the value of considering the nutritional effects from new crop strains.

“We hope to help facilitate that change in the future by bringing light and publicity to these varieties of plants that have enhanced nutritional properties,” Korth said. “Not only is there a market for it, but it also will improve the quality of life for people by giving them access to these staple crops, everyday foods, that have improved nutritional value.”

People can “still introduce more fruits and vegetables into your diet,” he said, “but also you can get components to feed your microbiome from the foods you’re already eating. That’s really a powerful thing, and it helps solve some of the nutritional deficits that we’re facing in the United States right now.”

The project’s findings connect directly to the mission of IANR’s Food for Health Center, whose research focuses on strengthening the scientific understanding of the relationships among food, health and the human microbiome. Korth is a research fellow with the center.

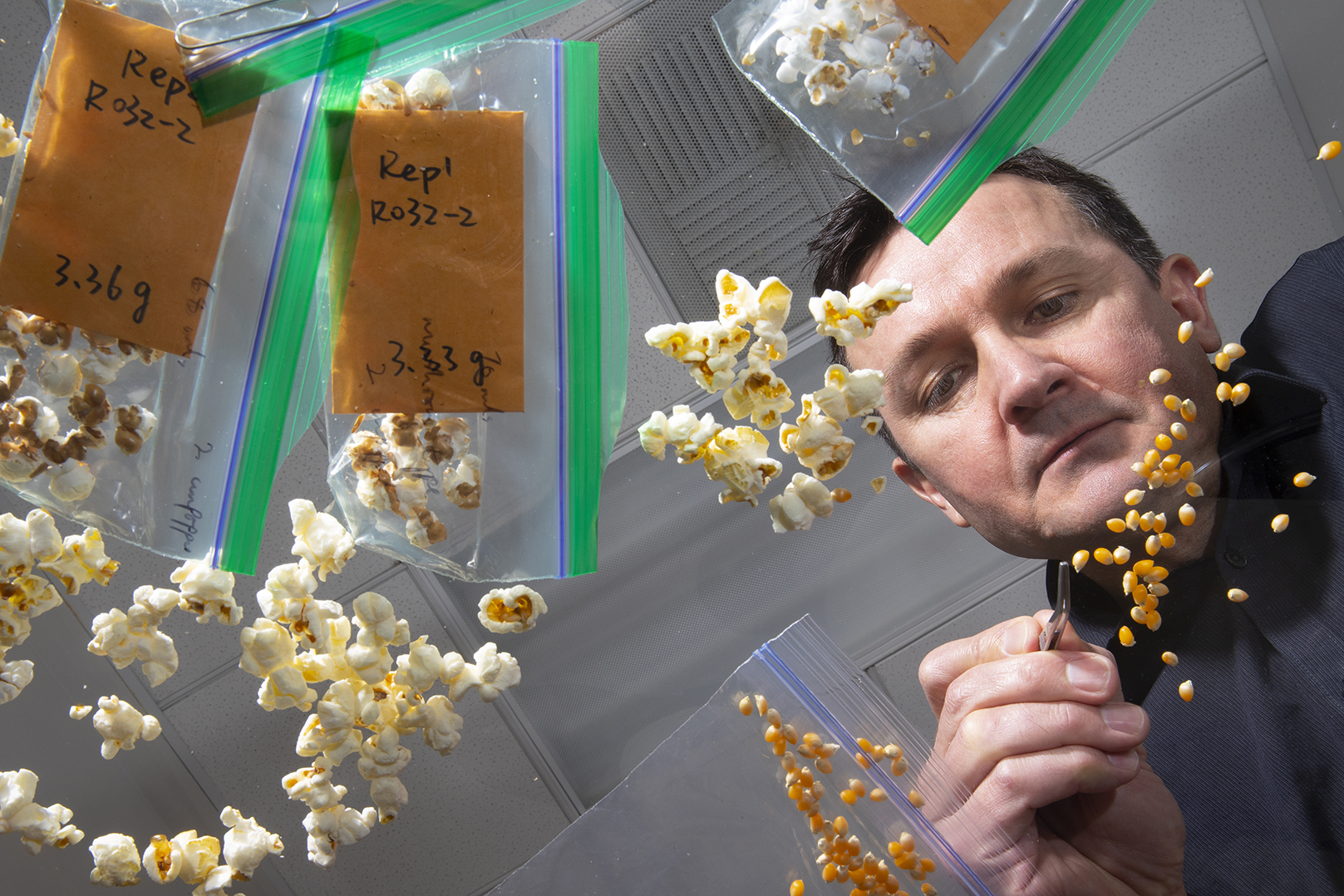

In addition to Korth, the IANR scientists involved in the popcorn nutrition study were Holding, Leandra Parsons, Mallory J. Van Haute, Qinnan Yang, Preston Hurst, James Schnable and Andrew Benson.

Grains such as corn, rice and wheat “can fulfill a significant proportion of total daily protein needs in both humans and animals,” they write in the journal article, but “the protein present in these grains is deficient in certain essential amino acids” that humans need to survive. The designation of an amino acid as “essential” means it isn’t produced by the human body on its own but instead must be obtained from dietary sources.

The popcorn variety Holding developed was naturally derived from a longstanding line known as Quality Protein Maize (QPM). This new QPM strain is rich in the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan, which are lacking in conventional corn varieties. The research article shows that certain human gut microbes can convert lysine to butyrate, a healthful fatty acid.

Previous scientific studies analyzed plant-derived sources of protein but not their influences on the human microbiome, Korth and his coauthors note. “In this exploratory study,” they write, “we have begun to fill this major research gap by testing the hypothesis that major differences in seed protein composition can have distinct effects on the human gut microbiome.” Filling in that scientific gap has growing relevance, they write, “given the increasing interest in plant-derived protein sources for foods.”

Nebraska has long been a national leader in popcorn cultivation. Producers annually plant more than 60,000 acres, yielding nearly 120 million pounds of the savory food. At present, opportunities for converting a portion of acreage to QPM are limited, given complications including the limited number of seeds.

Expanding the understanding of the connections linking food, human health and the microbiome is a promising area for scientists, Korth said.

“It’s just such an interesting area,” he said. “There are a lot of unexplored corridors, and it really piqued my curiosity. I think scientists, at their core, are explorers, and the microbiome is an unexplored area at this time.”

Scientists have pursued notable projects in that field in recent years, he said, but the landscape of unexplored research territory remains large.

For food science researchers, “there’s still a lot of work to do.”