It’s March 5, 1694, in Pisa, Italy. Vittoria della Rovere — grand duchess of Tuscany and member of the Renaissance’s first family, the House of Medici — lies immobilized at age 72. Her kidneys are failing, her legs swollen with fluid.

The grand duchess is dying.

What might she take to ease her discomfort in the hours before slipping away? More than 300 years later and 5,000-plus miles away, researchers at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln have an answer: cloves.

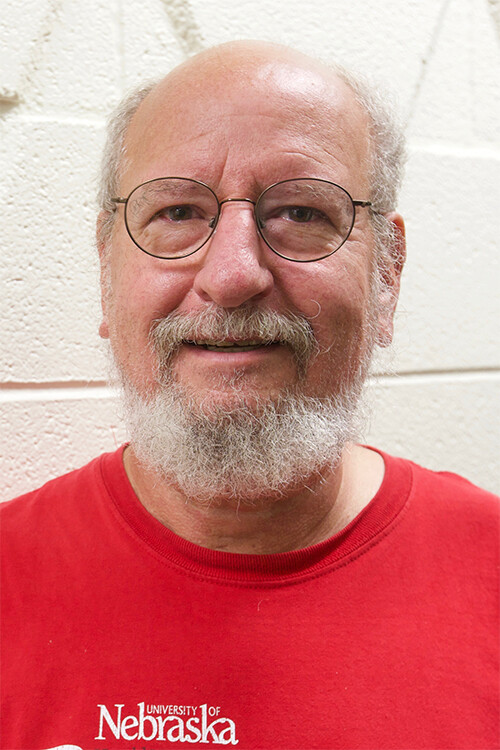

Led by Nebraska’s Karl Reinhard, an international team reached the conclusion after identifying pollen from an embalming jar marked with the grand duchess’ name and personal seal. That jar, exhumed from a long-overlooked chamber of the San Lorenzo Basilica in Florence, contained bits of intestinal tissue from della Rovere.

The presence, concentration and structure of the pollen grains found in that tissue suggests della Rovere ingested cloves — the dried buds of a flower native to the Spice Islands — shortly before her death.

“The question then was: Did she ingest the cloves, or was it part of the embalming process,” said Reinhard, a professor in Nebraska’s School of Natural Resources. “Cloves have a really nice scent, and perhaps they were washing her body with clove oil. But the fact that it was in the intestine — and that none of the other samples contained cloves — indicated that it was something she ingested.”

Some of the pollen grains in the intestinal tissue were clumped together, Reinhard said, suggesting that the cloves were boiled in water to make a tea. Clove oil contains a compound that acts as a mild anesthetic, and its ability to stimulate production of hydrochloric acid once made it a popular remedy for the digestive issues that della Rovere reportedly had.

Its use might also have stemmed from a less-heralded aspect of Renaissance culture that the Medicis helped cultivate.

“The Medici family was among the first to encourage Renaissance folks to plant botanical and medicinal gardens,” Reinhard said. “From that perspective, historically, Vittoria might have been reflecting a cultural practice that the Medicis got going during their Renaissance reign.”

Spice of life

By the time della Rovere died, ships had been carrying cloves from the Spice Islands of Indonesia to Europe for at least 900 years.

Her embalming jar, and the clove pollen within, took a similarly circuitous route. Samples from the jar initially traveled from Florence to three laboratories — one of them run by Reinhard’s longtime colleague, Dario Piombino-Mascali, in Lithuania.

Piombino-Mascali eventually sent the samples to Reinhard, who tasked students in a pollen-focused course with separating the intestinal tissue from the sponges and cloths used in the embalming. Several of the students also used a standard light microscope to investigate the structure and classification of the pollen.

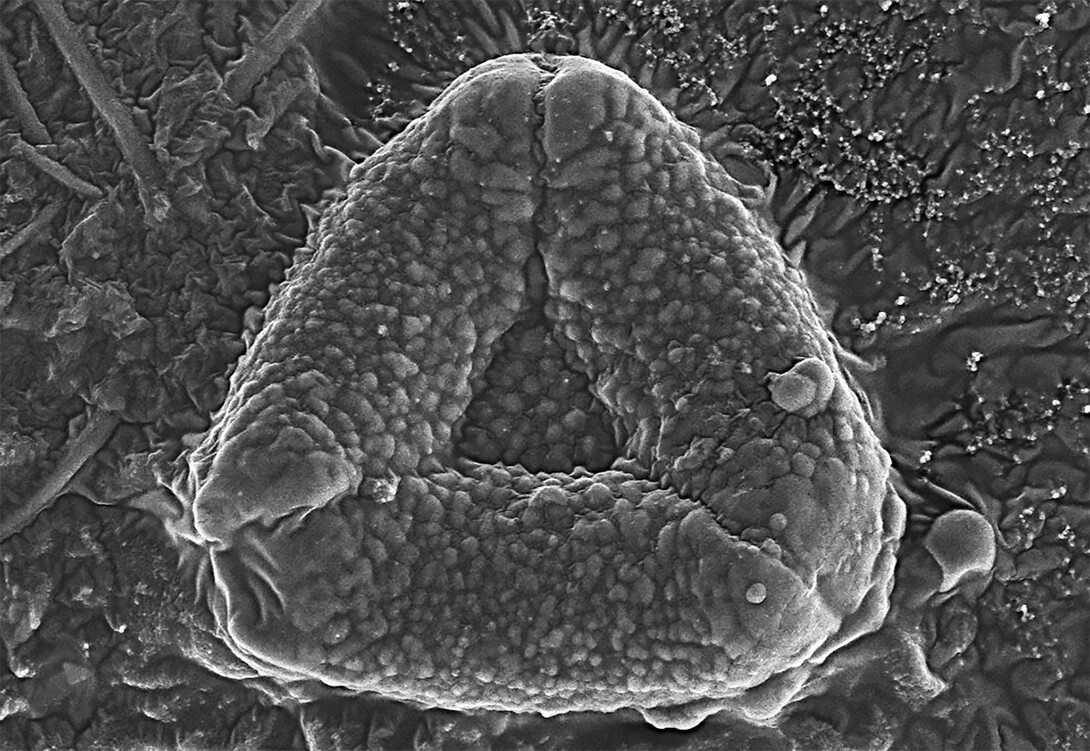

Their efforts revealed that the pollen from the jar belonged mostly to the Myrtle family of plants. That family’s notable members include eucalyptus and cloves, with Reinhard strongly suspecting the latter as the source. But the family’s notoriously small pollen grains — and thousands of species — made it difficult to pinpoint the pollen’s exact origin.

Then, a strike of good fortune: Upon submitting the findings to an academic journal, Reinhard was told that other researchers were about to publish comparisons of pollen from several major sub-groups of the Myrtle family.

Reinhard waited months, eager for the publications to appear. The wait was worth it. The researchers had used a scanning electron microscope, which strikes a microscopic or even nanoscopic structure with electron beams and then records how the structure’s atoms eject their own electrons. That technique produced renderings of the pollen grains at a much higher resolution than is possible with a light microscope.

Though the studies didn’t directly compare the sub-groups containing eucalyptus and cloves, they did give Nebraska’s You Zhou and Julia Russ — both experts in scanning electron microscopy — enough to help Reinhard complete the investigation.

“They’re triangular pollen grains,” Reinhard said. “They have a triangle in the middle, and then a line from each of the points of the triangle to the ends of the pollen grain. All you do is measure those lines and divide that by the overall length of the pollen grain. That gives you an index that you can use to identify the pollen.

“We finally had the metric data we needed (to confirm our suspicions). Combined with the fact that eucalyptus wasn’t introduced to Italy until about 150 years after (della Rovere) died, we were able to say for sure that they were from cloves.”

Reinhard was familiar with the history and mystique of the Medici family — the patronage of Michelangelo and Galileo, the raising of four popes — going into the study. But he derived just as much satisfaction from getting a look at the embalming jar as he did supplementing the history of della Rovere.

“My interest as a young archaeologist was pottery, so to see this ceramic vase with her seal and the label — and the remnants inside — that’s archaeological context,” Reinhard said. “I suppose that’s what matters to me: being able to put these specific human remains into a specific archaeological context. That brings it to life for me.”

The team published its findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Reinhard authored the study with Nebraska’s Leon Higley, professor in the School of Natural Resources; Zhou, research professor of veterinary medicine and biomedical sciences; Russ, research technologist with the university’s Center for Biotechnology; alumnae Kelsey Lynch, Annie Larsen and Johnica Morrow; and Braymond Adams III, graduate student in the School of Natural Resources.

Piombino-Mascali of Vilnius University (Lithuania), the University of Florence’s Donatella Lippi, and Marina Milanello do Amaral from the Instituto de Criminalística-Superintendência da Polícia Técnico-Científica (Brazil) also co-authored the study.