A maze of rodent burrows preserved in the walls of the Happy Jack Chalk Mine are providing information on the evolution of rodent behavior and a Great Plains ecosystem.

A research rarity, the burrows were found by Matt Joeckel and colleagues during a 2002 visit to the abandoned mine turned tourist attraction near Scotia.

“The project started out as a service call, which is a significant part of my job in the Conservation and Survey Division,” said Joeckel, a research geologist in the School of Natural Resources and professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “I was called up to provide some geological background for the group that manages the mine as an attraction.”

The visiting UNL group immediately noticed the burrows. Shane Tucker, highway paleontologist for the University of Nebraska State Museum, said the cross-sections on the walls were “simply amazing.”

“I would often sit there thinking about these underground tunnels, their interconnectedness and the amount of time invested in their creation,” Tucker said. “An engineer would be proud.”

The “chalk” walls of the mine are actually calcareous diatomite, a naturally-occurring, soft sedimentary rock that can easily crumble into a fine white to off-white powder. The sedimentary rocks are deposits of a late Miocene-era lake, Joeckel said.

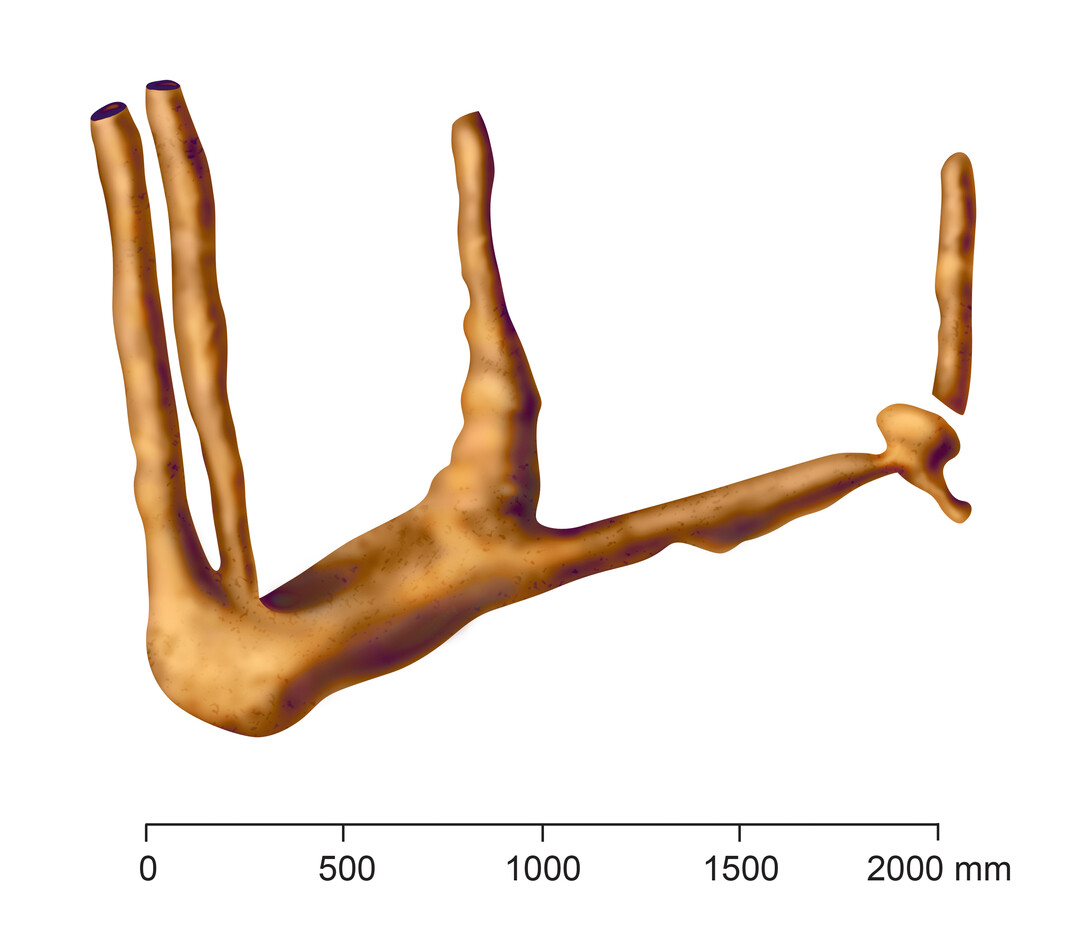

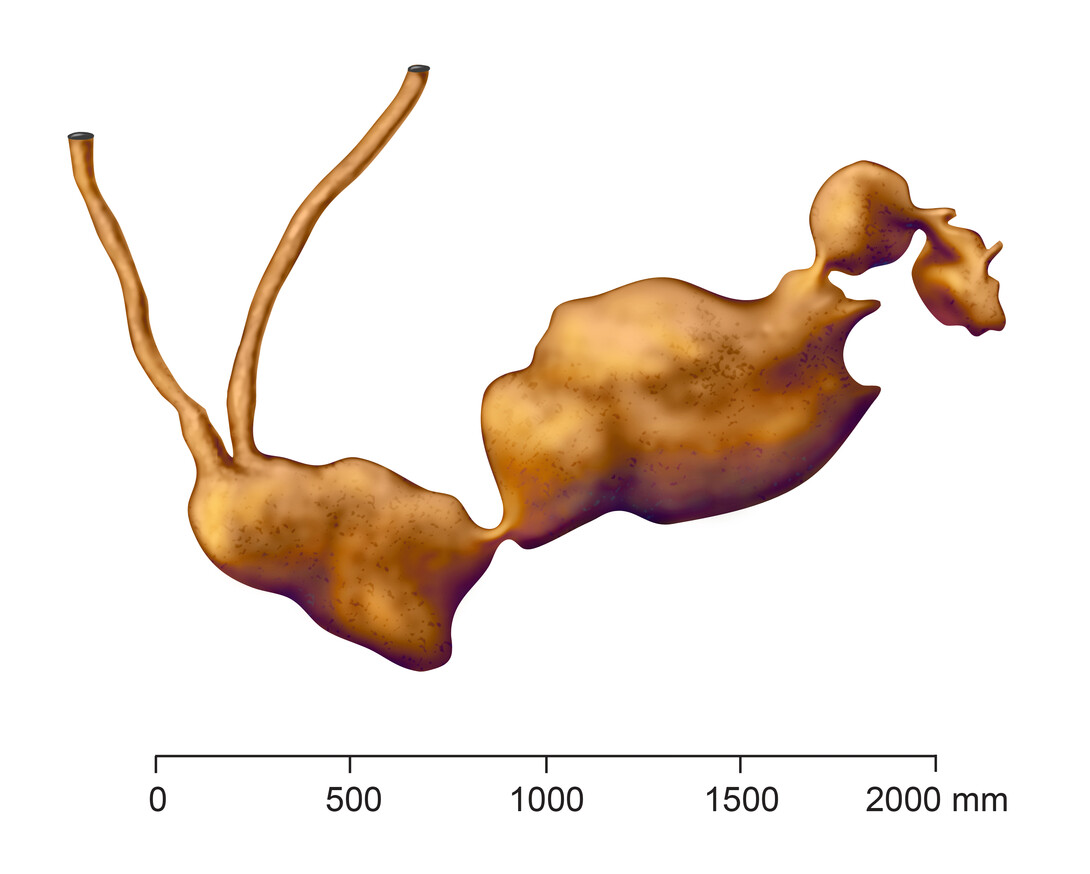

Fossil rodent burrows are what geologists broadly classify as trace fossils. They record the behavior of ancient animals rather than the actual preserved parts of organisms.

Joeckel and Tucker confirmed that both the burrows and the lake existed in the late Miocene Epoch, which extends from about 6 to 10 million years ago.

“We were able to verify that age assessment with fossils found in the mine and in equivalent deposits in the surrounding area,” Joeckel said.

Soon thereafter, they published a general paper on the deposits at the mine and its history of mining, which ended in the 1940s. The studying of the fossil rodent burrows, however, proved to be more demanding.

“We had to photograph and map the site underground — a difficult proposition under any conditions and a very unlikely research project in Nebraska, which has exceedingly few underground mines except for the operating limestone mines in the Weeping Water area,” Joeckel said.

Although they used electronic surveying equipment, operating the instruments underground was taxing.

“The major challenges of working at the mine included the dark, cold and damp conditions, as well as wearing a hard hat and ventilator all day,” Tucker said. “Mapping the entire mine to set up a framework for which to record the data was time-consuming yet rewarding as it was the first map of the mine.”

Joeckel and Tucker said the hard work was worth it, especially considering the magnitude — and uniqueness — of this discovery.

“The burrows themselves are a rare occurrence in terms of their excellent preservation and exposure,” Joeckel said. “So, in a sense, the site is a rarity within a rarity. This site was a major find.”

In their paper recently published in the journal Palaios, Joeckel and Tucker describe some of the most exceptional fossil mammal burrows in the world.

“This study is a tour-de-force, an informative and thoughtful examination of the evidence at hand, with fully substantiated inferences and conclusions,” said Larry Flynn, assistant director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University and one of the paper reviewers.

Flynn said that Joeckel and Tucker document the burrows thoroughly with statistical analysis of measurements, and called the study “authoritative.”

“They wisely note that more than one kind of rodent may have done the burrowing, and certainly not simultaneously,” Flynn said. “To an admitted fan of fossorial rodents, this paper is very welcome. It is also a basic reference for all who are interested in the late Miocene paleoecology of the Great Plains.”

The fossil rodent burrows record important aspects of rodent behavior as modern grasslands were emerging on the Great Plains.

While fossil rodent burrows are not particularly common in the rock record, burrowing rodents are considered to be a keystone species and ecosystem engineers in many biomes around the world today – like, for instance, grasslands.

“Certainly, without rodents, modern grasslands – including our agricultural lands on the plains in the USA – simply wouldn’t be the same,” Joeckel said. “In fact, it is likely that rodents and grasslands coevolved in places like North America.”

In short, the fossil rodent burrows represent not only the evolution of rodent behavior, but also the evolution of an entire ecosystem.

Joeckel said it’s likely that fewer than ten papers – that thoroughly describe any fossil rodent burrows of any age anywhere in the world – exist.

In the early 1900s, E. H. Barbour, the first acting director of the Nebraska Geological Survey, described one of the first fossil rodents ever: Daemonelix from early Miocene-era strata in northwestern Nebraska. And although Barbour incorrectly described Daemonelix as a plant fossil, the leap in knowledge is no less significant – both for geology and for the state of Nebraska.

“If we consider both the fossil burrows that we described and Daemonelix, as well as some Pleistocene burrows described by UNL graduate Rob Tobin, Nebraska could be considered famous for its record of ancient rodent behavior,” Joeckel said.

And there’s more to come.

“We’re planning even more research at the site in the future,” Joeckel said. “We want to find more fossil rodent burrows in the Cenozoic strata of the Great Plains and gradually work toward a longer-term picture of the evolution of grassland rodents and their behaviors.”