The intellectual war over modern agriculture has been won by the “cultural elite,” but agriculture’s continued commercial and technological success still bode well for its future, a political scientist said at UNL.

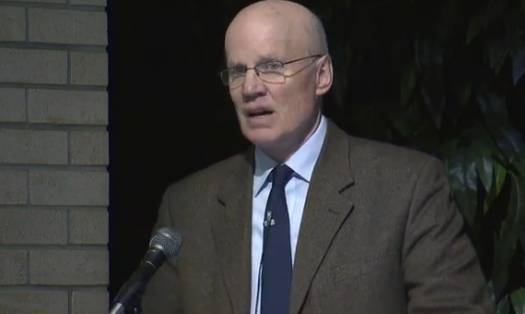

That’s not to say conventional agriculture won’t have to make adjustments in the face of ongoing challenges from its detractors, said Robert Paarlberg, who spoke at UNL on Feb. 27 as part of the Heuermann Lecture series. Specifically, he predicted that the inroads activists already have made in the area of animal welfare will continue to force change in livestock agriculture.

Paarlberg, the Betty Freyhof Johnson ‘44 Professor in the Department of Political Science at Wellesley College, is author of the book “Food Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know.” His lecture was titled “Our Culture War Over Food and Farming.”

Conventional agriculture as practiced in states such as Nebraska “is under strong attack” from people who believe it is unhealthy, unsafe, environmentally unsustainable and socially unjust, Paarlberg said. These forces want a shift from large-scale, specialized, highly capitalized farming systems to smaller scale systems that integrate crop and livestock production. Instead of internationally traded foods, they want local foods and instead of genetically engineered food, they want organic food.

Paarlberg said this battle is being fought on several fronts – intellectual, commercial and policy.

Conventional ag already has lost on the first front, he added.

“As for who’s winning in this cultural arena, I would say flat out the advocates for alternative agriculture have already won,” Paarlberg said. “Students come to my classes with their minds already made up.” They’ve taken in “Food Inc.,” Michael Pollan’s “Omnivore’s Dilemma” and other popular media attacks on modern agriculture and “they see this as a social cause.”

Paarlberg said he’s found one risks “social ostracism” by defending conventional agriculture in his state of Massachusetts.

In the commercial arena, detractors have made some progress in promoting changes in diets. Meat consumption and overall calorie consumption have dropped and a recent study shows the obesity rate among preschoolers is down.

“The activists’ critique of the way we eat … is having an impact … and I think that’s an impact we should welcome and celebrate,” Paarlberg said.

Activists’ promotion of organic agriculture and local marketing of food have led to advances in those areas too, but Paarlberg noted, they still comprise a very small percentage of conventional agriculture and international food marketing, respectively.

Meantime, most critics of conventional agriculture have ignored, perhaps as “an inconvenient truth,” the fact that their predictions that conventional farming practices were unsustainable have proven untrue.

In recent years, conventional agriculture has drastically cut inputs while continuing to increase yields. Total fertilizer use peaked in 1981, total pesticide use in 1973, Paarlberg said.

Technological advances have led to huge reductions in land use, soil erosion, irrigation water, energy and greenhouse gases, he added.

“If only the rest of our economy had done this well, we would have something to be proud of,” Paarlberg said.

Two areas where critics of conventional agriculture have scored significant victories are animal agriculture and the use of genetically modified crops for human consumption.

Ballot issues in some states, as well as decisions made by some large customers, have led to changes in how livestock are cared for, and that trend is likely to continue, Paarlberg said. Activists also are making progress in challenging the use of antibiotics in livestock solely for weight gain.

While genetically modified crops are used widely for animal feed and industrial use, they have “been stopped dead in their tracks for human food use,” Paarlberg said. Ballot issues to require mandatory labeling of foods containing any genetically modified ingredient failed in Washington and California and passed in Connecticut and Maine.

“Conventional agriculture will be obliged to make concessions,” Paarlberg concluded, but “those concessions aren’t going to push conventional agriculture away from its preferred model” of highly capitalized, large, science-driven practices.

Heuermann (pronounced Hugh-er-man) Lectures in the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources focus on providing and sustaining enough food, natural resources and renewable energy for the world’s people, and on securing the sustainability of rural communities where the vital work of producing food and renewable energy occurs.

The lectures are made possible through a gift from B. Keith and Norma Heuermann of Phillips, long-time university supporters with a strong commitment to Nebraska’s production agriculture, natural resources, rural areas and people.

Heuermann Lectures are archived at http://heuermannlectures.unl.edu shortly after the lecture. They are also broadcast on NET2 World at a date following the lecture.