Groundwater levels have declined in most of Nebraska following multiple years of below-average precipitation, University of Nebraska–Lincoln scientists found in a new statewide analysis. About three-quarters of the 4,787 observation wells across the state experienced groundwater level declines during 2021-22.

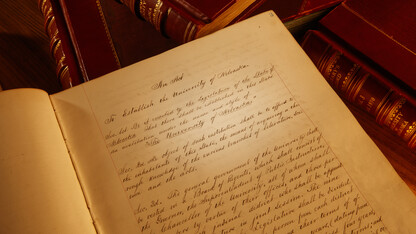

The Conservation and Survey Division, the natural resource survey component of the School of Natural Resources, compiled the findings in its latest groundwater level report.

For most of the observation wells, the net change in groundwater level was less than 20 feet since predevelopment times — before the widespread use of groundwater for irrigation.

Nebraska still retains a relatively abundant share of the High Plains aquifer system, in contrast to the situation in areas such as western Kansas and northern Texas, where the depletion of the aquifer has been severe, with major negative consequences for local agriculture.

But the survey’s findings highlight the direct negative effects that prolonged below-average precipitation can have on groundwater levels. During the 2020-21 period, 96% of weather reporting stations in Nebraska (166 out of 172) reported below-average precipitation. During the 2021-22 period, 68% of the stations (122 of 179) reported precipitation levels below the 30-year average.

The below-average precipitation values, combined with increased need for irrigation water to maintain crop yields, resulted in groundwater-level declines of more than 10 feet in some parts of the state, university scientists found.

“Changes in groundwater levels in Nebraska are largely dependent on annual fluctuations in precipitation,” said Aaron Young, survey geologist with the School of Natural Resources. “The hotter and drier a growing season is, the less water is available for aquifer recharge, and more water is required for supplemental irrigation of crops, resulting in groundwater-level declines.”

In contrast, wetter years mean that less supplemental irrigation water is required and more water is available for aquifer recharge.

Nebraska’s recent groundwater-level declines are concerning, Young said, in that some wells may need to be drilled deeper if drought conditions persist.

Although Nebraska has, on average, not seen declines in groundwater levels like those seen in Kansas or Texas, the degree of groundwater level change in Nebraska since predevelopment has varied greatly among individual areas, ranging from increases of more than 120 feet to declines of about 130 feet. For most of the state, the net change in groundwater level since predevelopment times has been less than 20 feet.

Parts of Chase, Perkins, Dundy and Box Butte counties, in contrast, have experienced major, sustained declines in groundwater levels due to a combination of factors. Irrigation wells are notably dense in these counties, annual precipitation is comparatively low, and there is little or no surface-water recharge to groundwater there.

The Conservation and Survey Division report was authored by Young and University of Nebraska–Lincoln colleagues Mark Burbach, Susan Lackey, Matt Joeckel and Jeffrey Westrop.

A free PDF of the report can be downloaded here. Print copies can be purchased for $7 at the Nebraska Maps and More Store, 3310 Holdrege St. Phone orders are accepted at 402-472-3471.