Four years in, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln research project has been successful at uncovering, digitizing and annotating thousands of documents from the Genoa U.S. Indian Industrial School in Genoa, Nebraska, and plans are being made to grow the project further.

The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project was founded to tell the stories of the American Indian families affected by the displacement of children to the Genoa school, often through force or coercion.

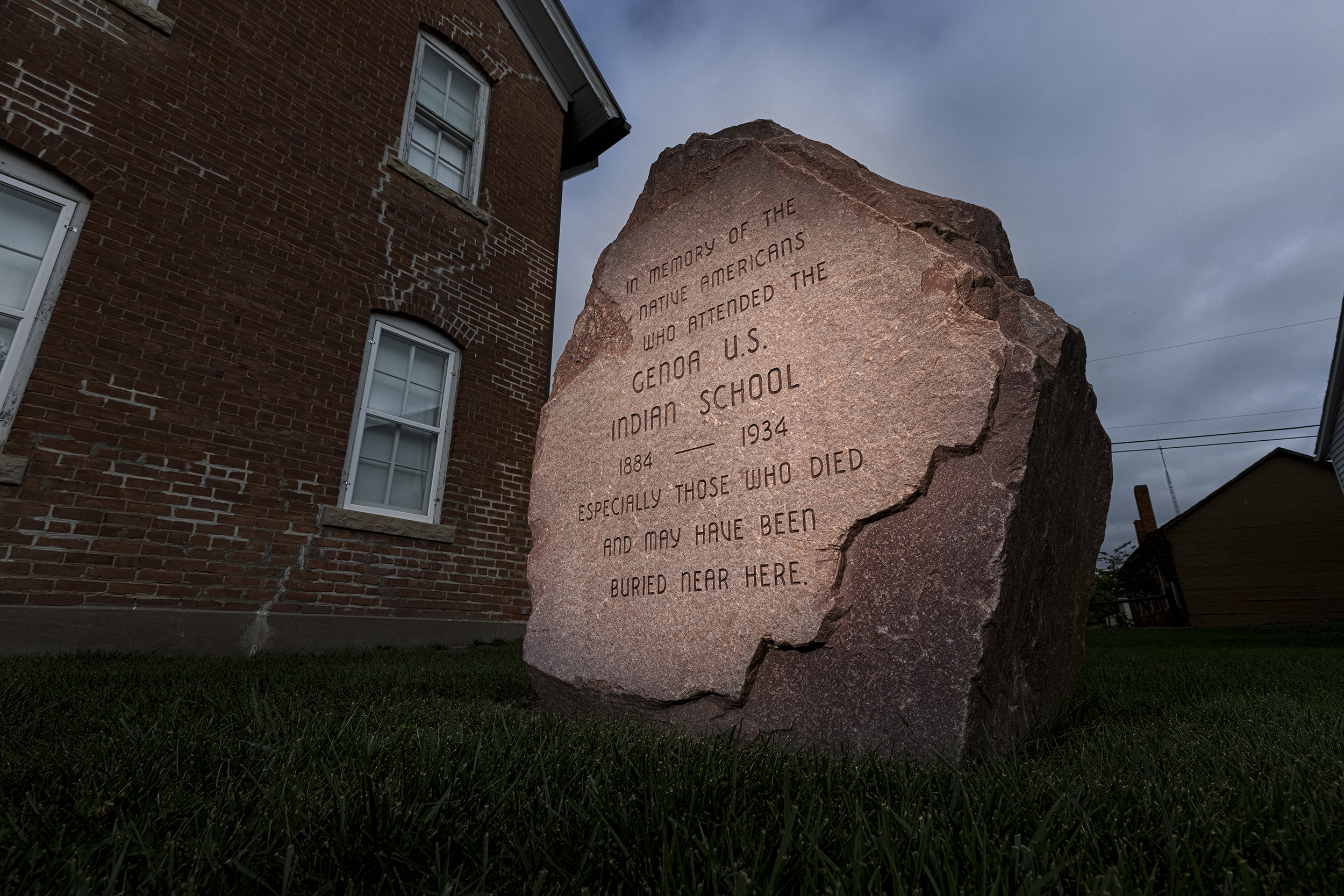

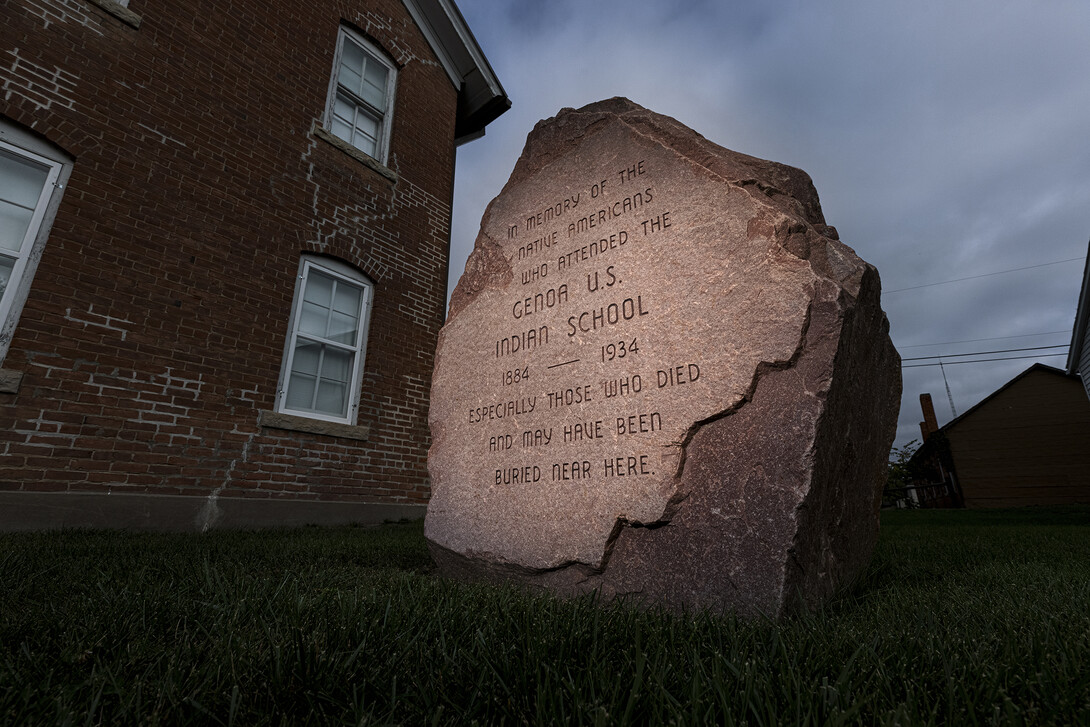

The Genoa school, which was run by the federal government from 1884 to 1934, was one of more than 300 similar schools throughout the United States — some run by the government, others run by churches. Researchers estimate that more than 10,000 children from 40 tribes were placed at Genoa during its operation, away from their families and culture.

“In the United States, until very recently, the majority of Americans had no idea about this history,” said Margaret Jacobs, professor of history, director of the Center for Great Plains Studies and project co-director. “I think a lot of non-indigenous people don’t understand the legacy of the boarding schools. It’s so important to understand because it created so much trauma for American Indian families and communities.”

The digital humanities project began in 2017, stemming from previous research by Jacobs on indigenous child removal in the United States, Canada and Australia. The reconciliation project is co-directed by Jacobs; Susana Grajales Geliga, assistant professor of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha; and Elizabeth Lorang, associate dean of University Libraries at Nebraska; and is overseen by a Community Advisors Council comprised of American Indian leaders.

Judi gaiashkibos, a member of the Ponca tribe, co-chairs the advisory council, which meets regularly with the research team. She said the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project is a step toward educating the public about the schools but, more importantly, helping Native families learn their own history and make sense of it.

“The goal is to find these records so that descendants like myself — I’m a survivor and descendant as my mother and two of her sisters attended the school — can look at these letters and records and from that, we can tell what really happened at the school,” said gaiashkibos, who also serves as the executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs. “We don’t think it was a lot of education.

“These schools existed to separate the children for the purposes of destroying the culture — it was cultural genocide. If you couldn’t eliminate all the people, then you went after their families, and you kept the children.”

A large bulk of research has been spent locating the records, which were dispersed after the school’s closure. The research team found various records in Kansas City, Denver and Oklahoma. Additional documents likely exist at the National Archives headquarters in Washington, D.C., and in archives in Texas. Trips will be made to locate those records when some COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. Also, through relationships developed with many of the tribes affected, the team has received records directly from families.

“We have found it’s extremely hard to find records of the Genoa boarding schools,” Jacobs said. “They’re not all in one place. They’re scattered around various national archives around the country, and they’re not well catalogued. I’m trying to use my skills as a historian, the archival skills I’ve developed over the years to try to find and locate those records, digitize them and make them searchable so that descendants of those who attended can find their relatives and find out what happened to them.”

The research team includes historians, librarians, digital humanities experts and students, both undergraduate and graduate. Geliga, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, began work on the project as a graduate student in history at Nebraska. In the course of her work on the project, she discovered her own familial ties to the school.

“I’ve worked in Native communities for years and years, and it would touch me at a personal level when I came across a last name that I’m familiar with, but it was also hurtful to come across my own family names,” she said. “As Native peoples, we have that information that each of our families have been affected by a boarding school experience, but it’s not always common knowledge to know that an ancestor went to a boarding school, because so many never wanted to talk about it.

“It wasn’t until my collegiate experience that I learned really how Native children were shuffled away to schools throughout the country.”

Aside from creating a repository for descendants to find information on their families, the project has unearthed new information about the school and the Genoa community.

“One of the biggest takeaways I’ve had, and this has just come very recently is, I always assumed the schools were separated from the communities in which they were in and that they were really aimed at segregating the children, not only from their tribes, but from the other children that might live in that area,” Jacobs said. “But the more I learned about Genoa, the more I realized it was an integral part of the community. It employed 500 people, which is remarkable.”

Researchers have also found records of death, many due to diseases that ran rampant in the overcrowded school.

“We’ve been disturbed by the number of children who died,” Jacobs said. “So far, we’ve found 59, and these were not in the government records. We found this information in newspapers, especially the student newspaper that was published on and off.

“We’ve found that the record of the rate of death of some of these diseases was much higher in the school than it was in the general population.”

One of the next steps is to locate the cemetery that was once on the grounds at the school. Jacobs said they’re unsure if it is still there or if it was disturbed, but it is a priority for the team.

Additionally, Jacobs said the digitization will be made searchable by name or family, and eventually will include oral histories.

“We want to do the personography, we want to find the children who died, and we want to find the cemetery,” Jacobs said. “We want to work with the communities and do oral histories of descendants, because they have a lot of stories that have been passed down to their families. That’s so important, because the government record, or the official record, is incomplete.”

The community will have an opportunity to learn more about the project from the researchers and advisory council during a special panel discussion at the Center for Great Plains Studies at 5:30 p.m. Nov. 11.