Welcome to Pocket Science: a glimpse at recent research from Husker scientists and engineers. For those who want to quickly learn the “What,” “So what” and “Now what” of Husker research.

What?

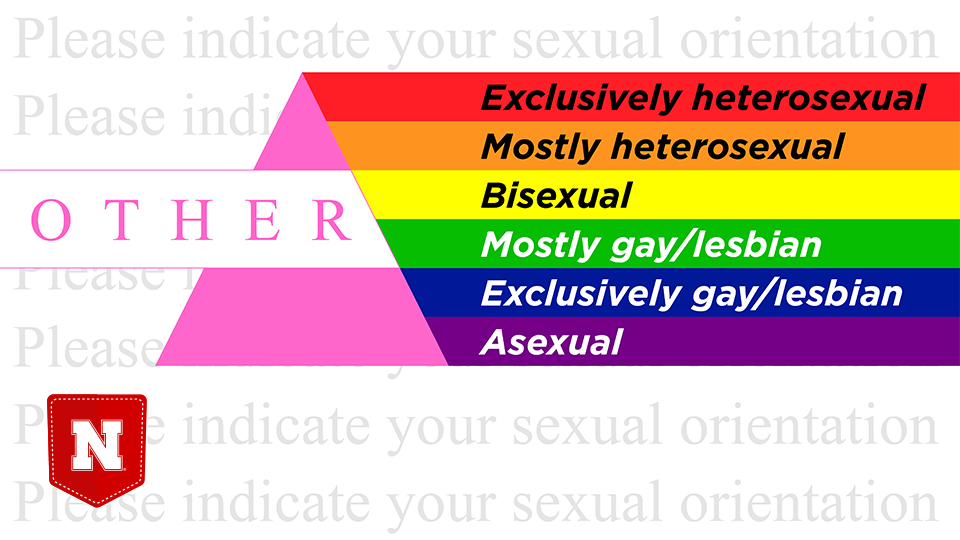

Surveys of many stripes ask for demographic information, including a respondent’s sexual orientation. To avoid straining attention spans, surveys will often limit their response options to just a few.

When it comes to sexual orientation, the options frequently consist of “Bisexual,” “Gay/lesbian,” “Heterosexual” and “Other” — with the latter intended as a catch-all for a variety of historically overlooked orientations on the wide-ranging sexual spectrum.

Prior research has suggested that some respondents in that sexual minority, rather than choosing the “Other” response, may instead select whichever of the specific responses best approximates their actual orientation.

So what?

Choosing a specific but less accurate response over the “Other” option could lead to misclassifications and underestimates of sexual minorities, who already face a relative lack of sexual health supports and higher risk of sexual trauma.

Lorenz found that 21% of respondents changed their orientation labels on the second question, most often to “Mostly heterosexual.” Of those who chose “Mostly heterosexual,” 78% had previously selected “Heterosexual,” with just 3% initially choosing “Other.”

The results suggest that “Mostly heterosexual” respondents, who probably constitute the largest sexual-minority group, are commonly being mischaracterized as strictly heterosexual.

Now what?

Expanding the number of sexual-orientation options on surveys could help address the problem of misclassification while only marginally increasing survey length and complexity.

Interviewing respondents to determine why they changed their responses, and how they interpret the labels, could also lend meaningful insights, Lorenz said.